“Millions of people will die because these ports are blocked”- David Beasley, Head of UN World Food Program.

While Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has brought the energy market to the forefront, it has also extrapolated other issues. A significant topic not getting as much media attention is the jeopardization of food security within both emerging and developed markets. Due to the war stress-testing several inputs that go into feeding the population, the world could be pushed into a global food crisis. This article will discuss the war's effects along with some suggested short and long-term solutions to today’s growing food insecurity.

Major Producers At War

Food security has always been an issue, even before the war in Ukraine. Problems such as growing demand, combined supply chain disruptions, currency devaluations, climate change impacts, and a rise in fragility and conflict affect farmers’ abilities to yield crops and feed countries worldwide. Unfortunately, the war has plunged the issue into the deep end by sparking several more disruptions. A considerable number of commodities that go into feeding the world are now being jeopardized as both Russia and Ukraine are major exporters of agricultural products, including wheat, barley, corn, rapeseed, and sunflower oil. Figure 1 shows the major wheat exporters, with Russia and Ukraine being number one and five, respectively.

Figure 1: World’s Largest Wheat Exporters

Together, Russia and Ukraine produce 30 percent of the world’s wheat exports and 60 percent of its sunflower oil. More so, at least 26 countries rely on Russia and/or Ukraine for more than half of their grains. Due to the war, Ukraine’s farmers cannot tend the fields and yield crops. The UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) has estimated that the war will leave 20 to 30 percent of Ukraine’s farmland unplanted or unharvested for the 2022 season. There is also the issue of already harvested and stored grain sitting in ports blocked by the Russian Navy. Figure 2 displays a map of Russian forces within Ukraine controlling any travel out of the Sea of Azov and the Black Sea. As a result, Ukrainian grain exports have been halted.

Figure 2: Map of Russian Forces Within Ukraine

Export Bans Multiply the Pressure

While Ukraine cannot get its exports out to the world, Russia is still free to supply the necessary inputs to produce crops. However, due to the war, Russia has decided to use food as a quiet weapon by banning exports of wheat, meslin, rye, barley, and maize to the countries within the Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU), except Belarus. Russia did not stop with grain products as they swiftly moved to halt exports of fertilizer that countries import to grow their crops. China performed a similar ban on fertilizer exports last summer due to rising global and domestic prices. To control and ensure the fertilizer industry within China would remain stable, the National Development and Reform Commission (NDRC) ordered major fertilizer companies to stop exporting. The desired effect was achieved as the price of fertilizer within the country began to fall; however, the global price was pushed farther up as the supply from China dwindled, as shown in Figure 3.

Figure 3: China’s Ban on Fertilizer Exports

With Russia and China banning fertilizer exports, prices have only risen. With fertilizer becoming more expensive, the effect does not bode well for countries that rely on importing to grow crops. For instance, Brazil, the world's largest fertilizer importer, is already having trouble getting enough nutrients for its produce. Moreover, the South American nation leads in global exports of soybeans, coffee, and sugar, which could be reduced in availability due to the higher prices. Examples of decreasing harvests are already being seen in France, where the agriculture ministry has announced it will cut corn plantings by six percent due to expensive fertilizers. As shown in Figure 4, France plans to sow the smallest land area in the last four years.

Figure 4: France Corn Plantings Shrink

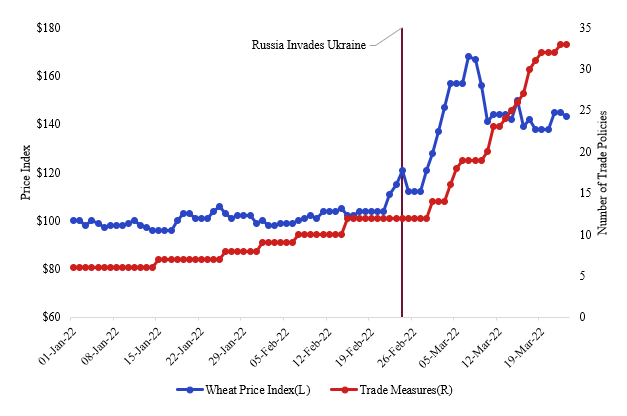

With growing prices and export bans by major agricultural producers, other nations are beginning to fear they will not have enough supply to feed their domestic population. As a result, counterproductive protectionist measures have started to develop in countries banning food commodity exports. By the end of March, 53 new food trade interventions were imposed. Out of the 53, 31 were restrictive to exports, and nine involved curbs on wheat exports. Figure 5 shows the progression of restrictive and liberalizing exports/imports from when COVID-19 began. The pace at which restrictive export curbs are rising reiterates the protectionist culture countries are adapting.

Figure 5: Restrictive Food Export Curbs Rising

More specific examples are shown in Figure 6, a summarized list of countries that banned food exports in the months following the beginning of the war. It is derived from the International Food Policy Research Institute. The complete list that includes other countries that have banned other items such as beef, butter, fruits, and vegetables can be found here. As governments continue to ban crucial exports, the global food supply shrinks, putting tremendous upward pressure on the price of food and food inputs, as discussed in the next section.

Figure 6: Countries with Food Export Bans

The Price of a Meal is Increasing

As the war rages on and countries worry about feeding their domestic population, the global food market continues to be stressed. The war has had a significant effect on the prices of agricultural commodities. For instance, in examining wheat, the price rise is nothing short of astounding and is amplified by the export bans, as seen in Figure 7.

Figure 7: Wheat Prices Rise Substantially

While wheat is a crucial input that goes into feeding the world, it is not the only one. In order to look at rising food prices from a 10,000-foot perspective, one can examine the FAO’s food price index. The index comprises an average of five commodity groups: meat, dairy, cereals, vegetable oils, and sugar. Figure 8 shows the index’s historical price along with the cereal and oil groups. To clarify, the cereal index comprises an average of groups of wheat, maize, barley, sorghum, and rice price indices. The oil index contains an average of ten different oil price indices. Meat, dairy, and sugar are similar in the fact that they are well diversified and show a fair overview of their commodity markets. For the complete description of each index, visit here.

Figure 8: Historical Price of Food Index

All three indices have increased substantially since the start of the war. The most recent report released at the beginning of June indicated that the food price index decreased slightly but is still severely elevated from a year-over-year perspective. This is most likely due to the rising prices in the cereal index, which is led by the surge in wheat, which has increased for the fourth consecutive month. Fertilizer followed the same pattern, rising nearly 20 percent from January to March.

The rate at which the price of food and food inputs are rising is affecting the world in both emerging and developed countries. The effects are felt more in countries with low to middle-income levels. As a typical, low-income family spends two-thirds of its income on food, it is becoming increasingly more difficult for them to afford to eat. The World Bank estimates that ten million people are thrown into extreme poverty for each one percentage point increase in food prices. If food prices stay elevated for the rest of the year, global poverty could go up by more than 100 million.

Emerging-market governments are feeling pressure from rising food prices. Food insecurity has morphed into a source of social unrest. There have already been protests in Sri Lanka, Tunisia, and Peru as governments cannot subsidize enough to keep up with rising energy and food costs. Developed markets are feeling the effects as well. Nearly ten million Britons cut down on food consumption or missed meals in April, and France plans to issue food vouchers to the poorest households. Figure 9 displays a world map with countries that are low, medium, or highly dependent on importing food to feed their domestic population. These countries will continue to feel the effects of the shrinking global food supply and rising prices. The following sections will discuss short and long-term solutions.

Figure 9: Countries’ Net Food Imports as a Percentage of Domestic Food Supply

Short-Term Solutions

Several entities have stepped up to try and relieve growing food insecurity. The World Bank stated that it is launching a financial package to provide support. It will give financial aid to countries, including Ukraine, that are hosting refugees, and developing economies suffering collateral economic shocks. It will begin with $50 billion in the current quarter (quarter one of 2022) and will reach about $170 billion in the 15 months following (in June 2023). The World Bank also stated that for price pressures to dissipate, both developed and emerging markets must reduce their export and import restrictions, which are artificially creating price hikes. The World Bank plans to encourage food production, enable market access and private sector investment, and protect the most vulnerable populations through well-targeted and cost-effective cash transfers. The bank also plans to mobilize two programs. The first is the Global Agriculture and Food Security Program (GAFSP), which G20 set up in response to the 2008 food crisis. The second is a multi-donor trust fund called Food Systems 2030, which can help countries strengthen their food systems to meet short and long-term goals.

Other governments have stepped up to provide funding and expertise in the fight. The U.S. Treasury met in April with multilateral institutions to discuss how to tackle food insecurity. The U.S. then decided to allocate funding to a new global food emergency package, bringing the total amount of assistance given for the issue to nearly $2.6 billion since February. More so, the U.S. plans to relieve the global fertilizer shortage with a $500 million program via the U.S. Department of Agriculture. Looking at other organizations, the Asian Development Bank stated that it, along with the FAO and World Food Program (WFP), will support efforts to feed Afghanistan and Sri Lanka. The African Development Bank will use $1.5 billion to help supply fertilizer and seed to 20 million African farmers.

In terms of the war, an estimated 20 million tons of agricultural products are stuck inside Ukraine. Before the war, the country could export grain and oilseed via ship at a rate of up to six million tons per month. However, about 80 percent of the world’s merchant ships are now stuck in Ukrainian ports, while the other ten percent have been attacked or hit by Russian assaults. More so, Russia now has four submarines in the Black Sea guarding any attempt to export any grain out. The EU is setting up a plan for Ukraine to export the commodities via rail. The union feels they can transport the 20 million tons over the next three months. However, there are severe bottlenecks at the borders as neighbors use different rail gauges. More so, if trucks were to be used, they could be hampered by drivers, fuel, and customs officials. Overall, the plan to exit by land will be much slower and could be dragged down by several bottlenecks.

Long-Term Solutions

Perhaps the shortest long-term solution would be for the ports within Ukraine, for instance, the port of Odesa, to be opened back up, which would immediately alleviate some of the price pressure in the global market. However, with Russia using food as a weapon, this seems unlikely until the war ends. With no knowledge of when this will happen or the outcome, it may be fair to say that it could be some time before Ukraine and Russia return to exporting food. Suppose the ports were to open without the war ending. In that case, it may take some extreme increases in food insecurity that would ultimately force Russia’s hand to make a peace agreement to let the ports operate without any interference from the surrounding battle.

The war will eventually end (hopefully), but the world will still be left with growing food insecurity and will need solutions to tackle it. Most long-term solutions focus on reducing food waste, attacking climate change, and improving infrastructure programs and trade policies. While food insecurity poses a threat, every issue is an opportunity, and this is no different. New ideas must be invented to create a more efficient system for feeding the world. However, funding, whether it is from private ventures, NGOs, or government entities, will be required to fulfill these solutions. The world must recognize that these innovations are needed and continue showing support for them.

Conclusion

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has pushed fears surrounding the ability of the global population to be fed. The ability to find efficient and timely solutions to growing food insecurity has never been more relevant than now. Governments and organizations must continue to search for the best possible ways to relieve the rising prices and shrinking supply. In the meantime, it is best to hope that the ports within Ukraine can open or that the war ends soon.

I hope you enjoyed reading as I enjoyed writing! If you want to learn more, the Financial Times has a great podcast: The Rachman Review, which recently had an episode discussing the crisis. I have included it here: