The infamous dot-com boom (and later, bust) is widely believed to have begun in 1995 with the IPO of Netscape, the company that created the first widely popular web browser. Netscape, co-founded by now-legendary venture capitalist Marc Andreessen, was an unprofitable company that strategically utilized positive PR to garner investor enthusiasm for their IPO. This PR effort effectively reached relatively inexperienced investors that contributed small amounts of capital to the public market, did not rely on market research when making investment decisions, and did not need significant returns on their investments to make an income (as public equity investing was only a supplement to their primary income sources). These kinds of investors are affectionately called mom-and-pop investors, because they are ordinary, everyday people with no specialized expertise in finance or accounting. As word of Netscape’s pending IPO spread across the country, these mom-and-pop investors urged their financial advisors and brokers to help them get in on the big IPO opportunity.

This was perhaps the first time that an IPO became a public spectacle rather than a topic of discussion within the more closed investor community. Sure enough, the immense demand for Netscape’s shares upon IPO drove its share price to more than double in its first day of trading. The power of mom-and-pop investors to drive up company valuations was soon realized by founders and investors alike; soon enough, many more Internet companies (many also unprofitable) went public with the support of both inexperienced and experienced investors. While company valuations continued to be driven up for many years, making some investors incredibly rich, many of the unprofitable companies that created these riches soon failed—a risk that was seldom recognized by even some of the savviest investors at the time. This marked the beginning of the dot-com bubble’s bursting—in which the aggregate market capitalization of U.S.-listed stocks dropped by a crushing $7 trillion, hundreds of thousands of tech jobs were lost, and the NASDAQ index fell by 75% from March 2000 to October 2002.

Today, another tech bubble may be forming and the lessons of the dot-com bubble may need to be revisited before it’s too late. To understand why there may be a bubble and why it may burst soon, it is important to first understand how this phenomenon comes to be and what specific factors may be driving today’s potential tech bubble. This article will then analyze key indicators of a bubble with respect to today’s conditions to determine if a tech bubble exists—a question whose answer will determine critical next steps for investors.

What are “Bubbles,” How are They Created, and What Causes Them to Burst?

A market bubble is characterized by a rapid rise in value of assets pertaining to a specific industry driven by immense positive investor sentiment. In a true bubble, prices of assets are driven far beyond their intrinsic value, meaning that the assets’ valuations far exceed their underlying value. American economist Hyman Minsky’s research yielded the concept of a five-stage “credit cycle” that illustrates how bubbles form:

Stage 1: Displacement

This is when investors notice a favorable opportunity that they could concentrate their capital on. This could be anything from a new technology or product to low interest rates or rising real estate values.

Stage 2: Boom

Demand for the asset rises, driving price increases. As these price increases are observed by other investors, fear of missing out (FOMO) sets in and more investors begin to enter the market. As more investors continue to join the market, demand increases and this drives prices to continue to rise.

Stage 3: Euphoria

When euphoria begins, asset prices skyrocket and investors take little notice of the risks they undertake when buying the asset. Caution is, for the most part, nonexistent in this stage.

Stage 4: Profit-Taking

Signs of a bubble become apparent to some investors and while it is nearly impossible to tell exactly when the bubble will burst, some investors will benefit from the greatly inflated prices by selling their assets while prices are still high.

Stage 5: Panic

Investor sentiment changes, and whatever the reason for this may be, asset prices drop dramatically. Oftentimes, prices fall just as quickly as they rose. Investors are willing to sell their assets at any price at this stage as demand rapidly declines.

To recap, investor enthusiasm for a particular industry or sector fuels the emergence of a bubble. This bubble grows as more investors participate in the given industry or sector (FOMO plays a significant role here). Real profit can be made if inflated assets are sold at the right time in the process (Stage 4). Those who don’t recognize the bubble or who do recognize the bubble but don’t sell in time, will experience rapidly declining prices, triggered by a significant decline in investor enthusiasm for the industry or sector.

Indicators of Today’s Bubble and What Could Cause it to Burst

As a bubble is defined by asset prices being far above their respective intrinsic values, what signs are there that this phenomenon is occurring in today’s public technology sector?

The Rise of Mom-And-Pop Investors

Today, inexperienced “mom-and-pop” investors are more numerous than ever before. With 13 million novice investors on Robinhood alone and over 20% of the total $50.8 trillion in capital in the public market managed by non-institutional investors, the effects of “mom-and-pop” investing (done in many cases without prior market research) have never been stronger. Public investing has, in the last few decades, become a topic of general interest, and when market research does not dictate investment choices, the influence of companies’ PR efforts do. As such, companies with the best PR strategies benefit the most from mom-and-pop investments. Furthermore, many companies today use PR specifically to promote their IPOs to the masses. Unfortunately, companies with the best PR do not necessarily have the performance to back up the hype.

Nonetheless, contrary to most valuations made in the private market, valuations in the public market are dictated by supply and demand. As such, the increased demand for shares of PR-savvy companies as a result of their efforts does in fact cause their prices to rise—dramatically in many cases. Often, these overvalued companies are in actuality a good investment in the short-term. After all, their prices are rising quickly and returns are being made. However, this valuation growth is not sustainable in the case of a bubble, because it is fueled more by the flashy effects of good publicity rather than the modest financial metrics that are far more indicative of intrinsic value. In the long-term, once investor enthusiasm naturally diminishes, so too will the value of companies whose valuation growth is based more on good PR than strong financial performance.

The dot-com bubble occurred during the largest increase in novice public investors as of that time, and the effects of mom-and-pop investors on the public market were largely attributed to the formation of the bubble. Now, apps like Robinhood are making public investing easier and more accessible to novice investors than ever before and some tech companies have used stock splits to make their shares more affordable to those investing smaller amounts. Leon Cooperman, billionaire founder, chairman, and CEO of Omega Advisors Inc. said that the rise of mom-and-pop public investors will “end in tears.” While the democratization of the public market serves the important benefit of providing opportunity to those who did not previously have access, it is hard to discount the role novice investors play in the formation and amplification of stock market bubbles.

Unprofitability

As can be seen on Figure 1, the correlation between the valuation of public companies and their profitability has diminished in periods where large bubbles have formed. Highlighted on Figure 1 are the period during which the dot-com bubble took place and the period during which today’s potential tech bubble has been forming. The discrepancy between the S&P 500 index and corporate profits was slightly greater in 2018 than it was at the peak of the dot-com bubble, suggesting that today’s potential bubble is more severe than the dot-com bubble. This lack of correlation between profit and market capitalization illustrates that this group of assets (tech stocks) is priced far above their intrinsic value (their profit)—a phenomenon characteristically indicative of a market bubble.

Some of the modern tech industry’s biggest ‘success stories’ are unprofitable while still growing their share price at exponential paces and commanding monumental market capitalizations. Here are just a few examples of companies with valuation growth that is not justified by their intrinsic value (profit) growth:

Tesla has made no annual profits until 2020, endured over $5 billion in net losses prior, and has had its market capitalization grow by 26x since 2015 (from $31.54 billion to $834.17 billion as of January 7th, 2021).

DoorDash has made no annual profits since at least 2018, lost about $1.5 billion since 2018, and experienced about a 2.25x jump in valuation since just before the company’s IPO (from about $16 billion pre-IPO to $37.27 billion today).

Airbnb has never made an annual profit, reported $1.04 billion in net losses from 2015 to 2019 (2020 financials unavailable at time of publishing), and grew in valuation by almost 5x since just before the company’s IPO (from about $18 billion pre-IPO to $88.36 billion today).

Fastly has lost $114.94 million from 2017 to 2019 with no annual profits in that period or 2020, and grew in market capitalization by over 500% from 2019 to today (from $1.9 billion December 2019 to $9.65 billion today).

Uber has suffered $17.05 billion in losses from 2015 to 2019 with only one profitable year in that range (2018). Nonetheless, Uber’s valuation has still almost doubled since 2019 (from $51.05 billion January 2019 to $93.97 billion today).

Palantir has never been profitable in its 17 years of operation and has lost hundreds of millions of dollars each year of its lifetime. Palantir grew in value by over 10x from its IPO in September 2020 to today, even while eliciting immense controversy (grew from $4.72 billion at IPO to $48.53 billion today).

Snowflake has lost $526.57 million in the last two years, with no annual profit reported in 2019 or 2020. However, the company’s valuation has grown over 850% since September 2020 when it went public (grew from $9.72 billion at IPO to $83 billion today).

There are many more companies that have similar disconnects between profit and valuation. The failure of any and all of these unprofitable companies may become a catalyst for the decline in investor sentiment for the tech sector that will burst the tech bubble. Once investors are reminded of the risks associated with financing unprofitable companies, they may pull their money out of other unprofitable companies (which depend on financing cash inflows to survive) on a mass scale, causing yet more businesses to fail, employees to be made jobless, and people invested in these companies to lose all of their returns. The inflated value of these unprofitable companies imploding is just one possible scenario that could cause the tech bubble to burst.

High Price-to-Sales Ratios, Weak Operating Cashflows, and Valuations at Absurd Revenue Multiples

The price-to-sales ratio (market capitalization divided by the last 12 months’ total revenue) is a key metric for evaluating the price of a company. The lower the ratio, the more attractive an investment the company is. The higher the ratio, the more overpriced the company’s valuation is. High price-to-sales ratios across the market are indicative of a bubble, as they illustrate a large gap between companies’ intrinsic values (using revenue as a measure in this case) and their actual prices (market capitalization). The dot-com bubble beginning at 1995 and ending around 2002 can clearly be seen in Figure 2. Today, the S&P 500’s price-to-sales ratio is significantly higher than dot-com bubble levels. This indicates that there is a tech bubble now, as there was the last time the S&P 500 index’s price-to-sales ratio was this high.

Revenue is certainly a more generous measure of a business’s intrinsic value than profitability is, since it doesn’t take into account the costs of the business. However, even with an emphasis on revenue as a indicator of intrinsic value, tech companies today are still incredibly overpriced.

Another metric that can be used to determine a company’s intrinsic value is net operating cashflows. Cashflows are important because they dictate how much cash a business has to pay off its expenses and how it is obtaining this cash. Without a reliable source of cash, companies go out of business because they cannot pay for incurred costs. Operating cashflows are considered far more reliable and sustainable in the long-term than financing cashflows, because strong operating cash inflows give a business financial autonomy, show that the business’s internal costs can be covered by the business’s operations alone, and demonstrate that the business does not regular cash injections through financing to continue operations. Many companies today are relying heavily on financing inflows to continue operations because, among other reasons, they do not have the operating cash inflows to become financially autonomous. Relying on financing cashflows too heavily is dangerous because if, for whatever reason, investors cannot be counted on to fill ever-increasing financing rounds, the business does not have the cashflows it needs to continue operations.

Here are just some of the many examples of companies today that are overvalued with respect to their revenue:

Zoom is valued at a 126x revenue multiple (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue).

Tesla is valued at a 30x revenue multiple (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue). Tesla also had operating cash inflows of $5.4 billion in that period, contrasted against their $14.35 billion in financing inflows.

Snowflake is valued at a 166x revenue (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue). In this time period, Snowflake had operating cash outflows of $116.9 million with financing inflows of $5.67 billion.

DoorDash is valued at a 28x revenue multiple (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue).

Snapchat is also valued a 39x revenue multiple (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue). Snapchat had operating cash outflows of $474.05 and financing inflows of almost $3 billion in this period

Airbnb is valued at a 26x revenue multiple (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue).

Fastly is valued at a 39x revenue multiple (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue). Fastly had operating cash outflows of $43.23 million and financing inflows of $747.37 million in this time period.

Palantir is valued at a 43x revenue multiple (Q4 2019 - Q3 2020 revenue).

Clearly, these companies (and many others) are not only overvalued, but likely cannot sustain themselves without financing. The condition of companies being overvalued perfectly resembles the disconnect between intrinsic value and pricing that characterizes a market bubble. The weak operating cash flows and prevalent high financing cash flows illustrate that these companies would be quite vulnerable should they be unable to rely on investments to sustain the company, and that today’s market, being bolstered by such vulnerable companies, is unlikely to continue its exponential growth without a serious correction.

IPO Mayhem

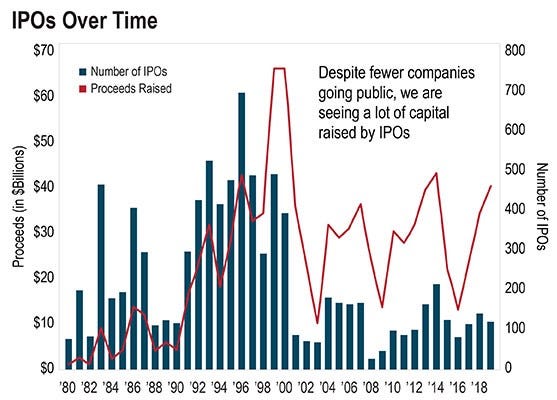

As Figure 3 illustrates, ever since Netscape’s IPO which for many marks the beginning of the dot-com bubble, the IPO market has changed fundamentally in that despite IPOs per year declining, the amount of capital raised by IPOs each year has continued to be disproportionately high compared to the number of IPOs. This suggests that the strategy pioneered by Netscape of getting big fast (by revenue standards) regardless of costs ensued or capital necessary, IPOing, and using PR to bolster share price upon IPO has been frequently used since the Netscape IPO and the subsequent dot-com bubble.

Since Netscape proved that using PR to promote their IPO to mom-and-pop investors successfully inflates company valuations, a higher percentage of IPOs than ever before have been unprofitable companies. This is despite declining numbers of IPOs per year. As Figure 4 shows, for the past 5-6 years, the percentage of unprofitable company IPOs compared to overall IPOs each year has been at dot-com bubble levels, steadily rising from around 50% during 2014 to about 80% in 2020.

Cross-referencing Figures 3 and 4, if you combine the high capital concentration in a smaller amount of IPOs and about 75-80% of today’s IPOs being unprofitable companies, it is clear that underwriters and post-IPO investors are taking on an unprecedented amount of risk. This is due to the lessened diversification that comes with the lower amount of IPOs, the disproportionately larger investment amounts per IPO, and an average of 75-80% of these investments being in unprofitable companies that cannot survive on their own without periodic financing. Underwriters and other public investors may see significant losses when or if the stock market crashes, especially if the crash comes with the failure of many of today’s big-name, unprofitable companies.

The Course of Events Fits Minsky’s “Credit Cycle”

Displacement:

The seed for today’s tech bubble was planted by early-stage investors. As can be seen on Figure 5, the ongoing increases in the venture capital industry’s amount invested each year began in 2014. Consistent with today’s IPO market, today’s VC market is concentrating a disproportionately high amount (even when compared to the dot-com bubble) of capital into a smaller number of deals. While VC investing has risen far more steadily in the past 7 years than it did during the dot-com bubble, the amounts invested each year by the VC industry are unmistakably differentiated from other periods where the amount invested by VCs stayed relatively unchanged over time.

Figure 5 (Source: Statista) Venture capitalists, preceding today’s potential tech bubble, exhibited a clear preference as to what industries they invested in. This is consistent with the displacement stage of the credit cycle in which investors concentrate capital towards certain assets (in this case, technology startups). Figure 6 shows that almost 50% of VC deals (during 2010-2016 in the top 20 VC-backed industries by deal count) contributed capital into the Internet Software & Services industry, with 95% of deals contributed to either software or hardware companies. These VC-backed companies became today’s public technology companies.

Figure 6 (Source: CB Insights)

Boom and Euphoria:

Boom occurs when more investors are quickly joining in investing in a given asset, and with this increased demand comes increasing valuations of the asset. The S&P 500’s value started to noticeably incline around 2013 before the Euphoria stage began in which prices skyrocketed with rapid increases in demand for tech stocks. Euphoria continued through the coronavirus pandemic as investor optimism drove the market’s quick recovery from the big hit it took when COVID-19 entered the United States.

Figure 7 (Source: New York Times)

Profit-Taking:

Should there be a tech bubble, I believe we are currently in the Profit-Taking stage. This is where savvy investors or those that suspect a bubble exists cash out of their investments and benefit from peak pricing. Hedge funds are reportedly dropping tech stocks in favor of stocks with more favorable valuations. Analysts from Princeton and Harvard argue that hedge funds rode the dot-com bubble to its peak, while avoiding significant losses by selling prior to the price collapse during a window before investor sentiment predictably changed. If this is true (and it probably is), hedge fund activity may be an indicator of when the bubble is about to burst.

If there truly is a stock market bubble, we still have the Panic stage ahead of us - and if hedge fund activity and recent analyst ratings can correctly be interpreted as warning signs, the Panic stage is coming soon.

Works Cited

Lyons, D. (2017). Disrupted: My misadventure in the start-up bubble. New York City, NY: Hachette Books.

Thank you for another interesting and thoughtful article.

Informative!