The Damage to Wealth

A dismal end to a quarter and what comes next? Demographics give us clues

As we reach the summer solstice, most market and specifically crypto investors have been praying for the days to shorten, but alas, we likely have more gloom in the near-term as interest rates continue to rise.

The US Central Bank conducted the biggest interest raise since 1994 last week, which has undoubtedly spooked investors as evidenced by the headlines running with this narrative.

But rightfully so; paying more than $5 a gallon for gas may have been the norm in California for some time, but even in places with less aggressive oil regulation we have seen the average gas price rise like a rollercoaster with no dip. Inflation is being felt everywhere.

All this is happening as the Central Bank’s credibility teeters, with public trust actually having been at peril for sometime (53% of Americans say they don't trust the central bank, and this was in 2021).

This is not a playbook for what central banks should do next, but more so an exploration of what demographics show us regarding the transfer of wealth, which has not been looking so good recently.

Even with the market sell-off in recent weeks, wealth is abundant, but what happens to wealth over time?

The Population Boom

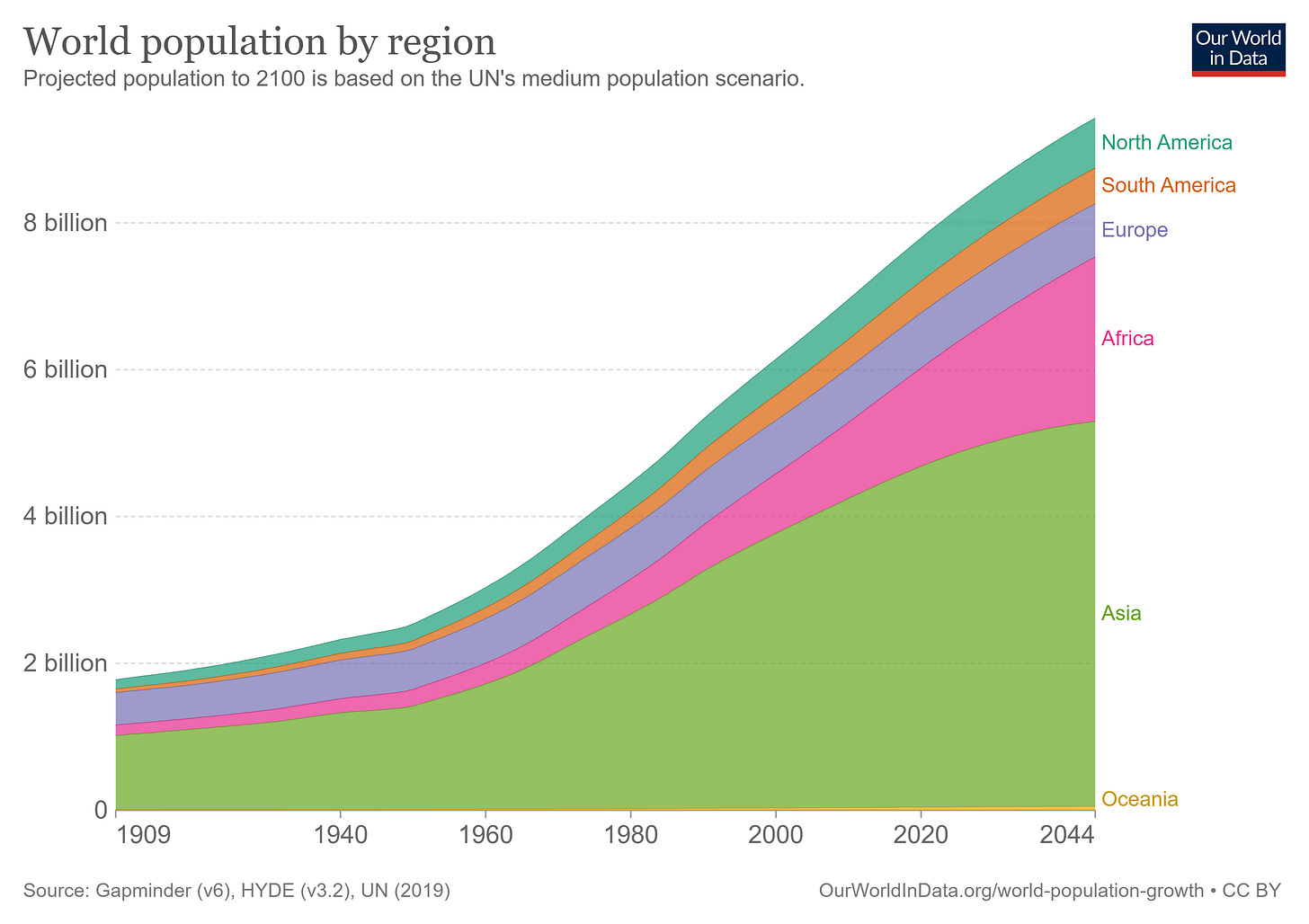

After the end of two world wars we were treated to a sizeable increase in population growth from the generation we have dubbed the Baby Boomers.

As this generation nears retirement, its important to understand the implications this brings forward.

Prior to the Baby Boomer generation, the population slope had never experienced quite the upheaval it has now seen for the last 70 or so years. You would think that being born into a cohort with more people would lead to more competition for jobs, housing, social programs, spots in good schools, and on a macro level, more competition for things as basic as natural resources. So how did this generation of people from the largest population explosion ever, end up in aggregate, very wealthy?

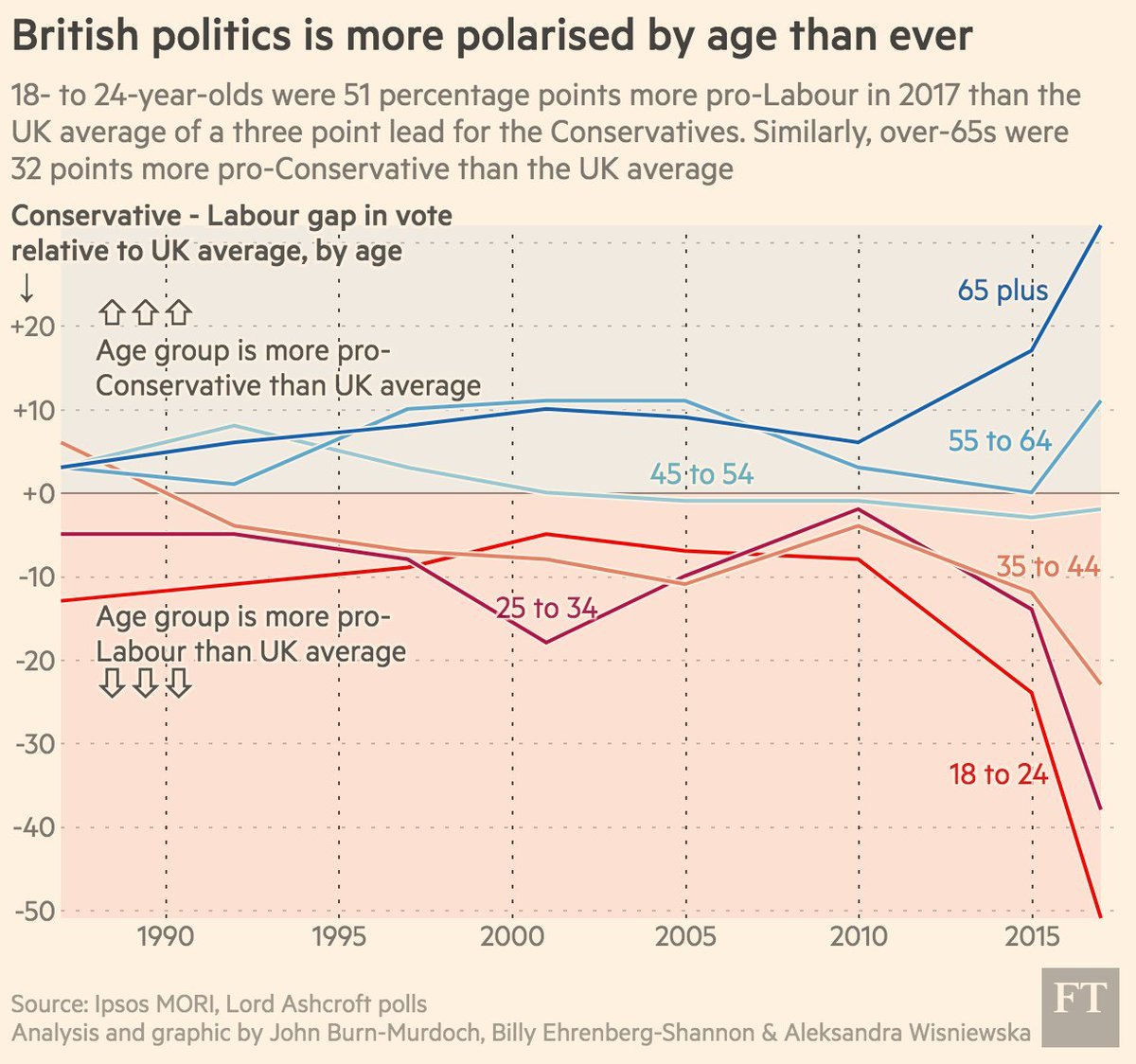

Interestingly enough, David Willets wrote the book “The Pinch: How the Baby Boomers Took Their Children's Future - And Why They Should Give It Back”. In his book, David alludes to the idea that in a democratic system being part of a larger cohort is actually preferable because it gives that group more voting power on generational issues and more sway in marketplaces. When the Baby Boomers were young, they voted for policies that benefited them, such as low cost or free higher education, family support systems, and strong social welfare. When the Baby Boomers got to the peaks of their careers, their voting patterns changed again.

Just take a look at the divide between the age of voters in the UK in the last decade alone.

This leads us to where we are today, with a projected $70 trillion in assets expected to be handed down over the next two decades.

The Transfer

Properly addressing and managing the transfer of a generation’s wealth could be the make or break for an economy. If it is not handled correctly, we could genuinely see assets and businesses go without the stewardship they relied on with their previous owners. Regardless, all of this money changing hands is bound to give a boost to the wallets of a younger generation which has famously been saddled with economic headwinds like student loan debts, stagnant wages, and turbulent job markets.

You might be forgiven for thinking “this is great, it is going to finally give my generation the healthy financial boost they need to unsaddle themselves from debt, or even just become bigger spenders/investors.” While there are definitely going to be some good things that come from this transfer, it may not be all good news.

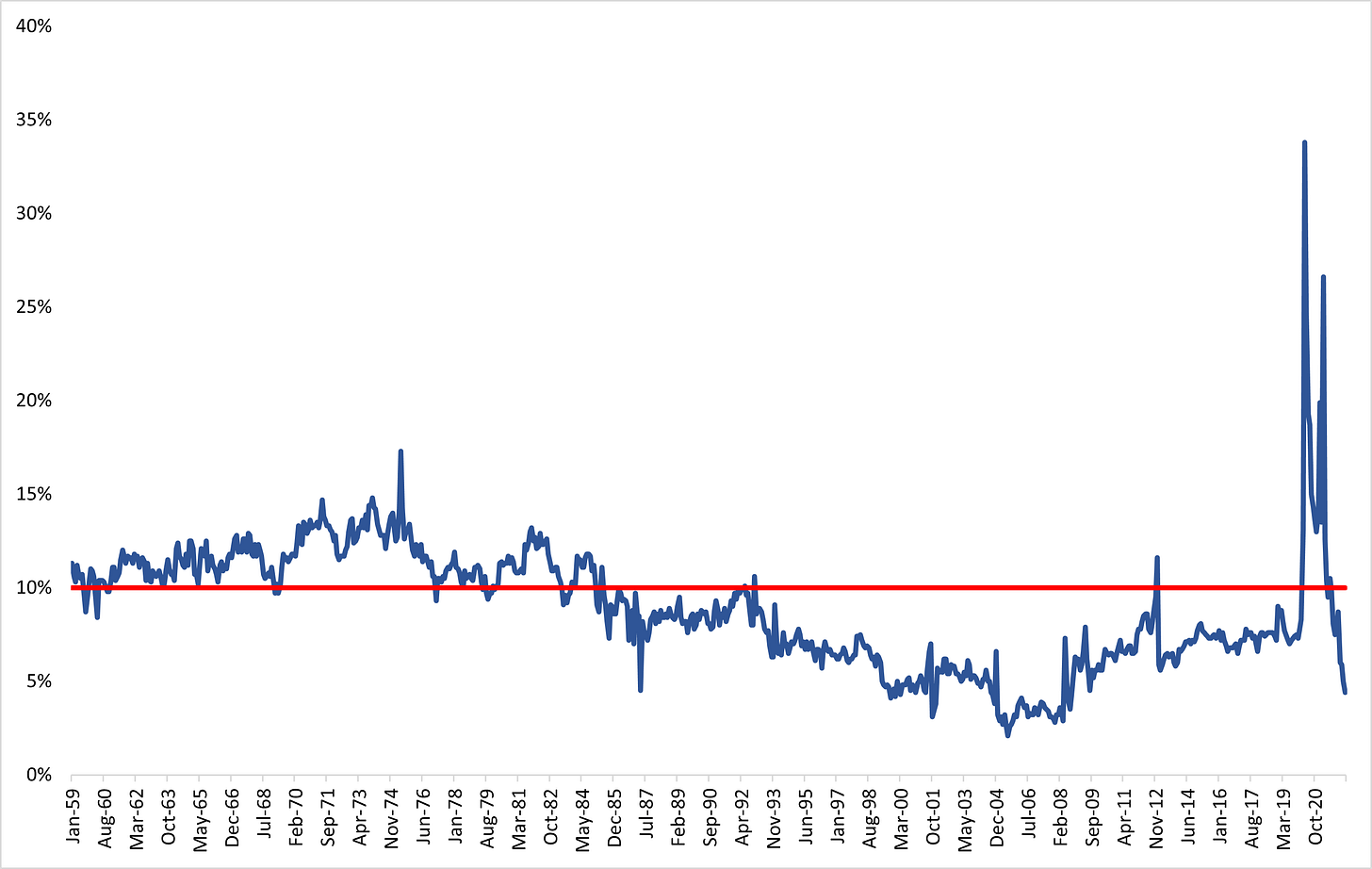

Starting with savings, the graph below shows the U.S. Personal Savings rate since the index began. Other than a couple of spikes in December of 1992 and December of 2012, we have not seen this metric rise above 10%: an ode to spending pressures and good marketing that capitalism has produced. Of course you are probably thinking: “What about 2020?” Well, we all know it shot up due to unique market conditions rather than long-term, sustained macro trends. If I had to guess, the pre-existing downward trend only continues into the future.

To add insult to injury, smaller inheritances are more likely to be squandered.

Obviously it is easier to spend less money than it is to spend up more money, but it more has to do with where this money goes.

If I received an inheritance of $50,000, it wouldn’t mean I could quit my job, or even purchase a home with straight cash at this point… (I say this from the perspective of someone living in the US).

Of course, $50,000 would be a fat deposit for a house pretty much anywhere in the world, but it would still be up to the recipient of the inheritance to qualify for financing for the remainder of the purchase price.

An asset-based inheritance may give someone an injection of cash, but it doesn’t increase their incomes or polish up their credit score, so more often than one would think, it is difficult to deploy this capital effectively.

Also, despite the GameStop and r/investing craze from the pandemic, only 58% of Americans have funds invested in the stock market (89% with a household income greater than $100,000). Additionally, only 35% said in 2019, that they had anything invested outside 401(k)s. Another important point to note is that while the median inheritance size is $69,000 dollars, the average inheritance size is over $700,000.

What this means is that a large majority of this wealth transfer is coming from, and going to wealthy households. A lot of this wealth is tied up in small businesses and respective owners/trustee recipients.

How many examples are there of businesses out there that have been successfully run by a CEO after they were promoted into that role from their previous position as son of the CEO?

Of course, successful handovers do happen but reputations exist for a reason.

A US Census Bureau study found that 66% of family businesses do not survive the transition from the first generation to the second, of those that do survive, only 50% then make it on to the third generation. But like I said earlier, the real bulk of inheritance that will likely be of global impact rests in the form of trusts and the dubbed ‘trust-fund babies’ receiving the above-average inheritances.

Most developed nations in the world today have some form of estate tax that is levied on the passing down of assets. This includes the US, where there is a federal tax of 40% charged for estates over 11 million dollars in value. Of course, given this high value, the charges don’t apply to 99.9% of inheritances but for those that it does apply for, those charges are pretty steep. So, naturally when Uncle Sam comes knocking at the door looking for his ‘fair’ share of the estate, the great American has improvised and developed a whole industry around this to shield themselves, where firms like insurance companies will offer life insurance policies to cover the estate tax burden.

Beyond this, it must be recognized that the actual valuations given to family companies can be pretty fluid and more often than not these institutions are valued lower than they probably should be for reporting purposes.

Even more to the point, an 11 million dollar family business would likely have some kind of succession plan in place with pre-existing employees in executive positions. The argument for an estate tax is that while it might cause some turbulence in large institutions during a transition phase, that can be planned for, even if it means taking on a loan, selling some shares in the business, or sitting down with an estate lawyer and jumping through some loopholes.

This tax provides strong revenue from people that can afford to take the loss while also reducing the tax burden on smaller businesses or regular folks that might only get few thousand dollars in their trust fund. So, it will continue coming down to the government primarily to redistribute this wealth over the next two decades. The bigger question is where? Student Loan Forgiveness? Public Infrastructure? The Agriculture Industry?

If anything is to be taken away, it’s the fact that around the globe, wealth will be transferred abundantly over these next decades, and it will be messy, sketchy, ugly, and all of the above. But what will the government do? More importantly what will we do? Are we to make policy decisions that favor us in the moment or will we think longer-term?

"Planning for the future without a sense of history is like planting cut flowers." -Daniel J. Boorstin