The Growth Drivers and Inhibitors of the B Corp Movement

Academic Research Adapted: What the B Corp Movement is and What Drives or Constrains Growth in the Movement

INTRODUCTION

Today’s global citizens face unparalleled challenges that are complex, global in nature, and deeply in need of solutions produced from interdisciplinary collaboration. Heightening concerns about global warming, growing calls for social justice and public policy reform, and the strain of our global population size on increasingly finite resource pools characterize the challenges – and opportunities – that face businesses today. Because corporations as a whole are by far the largest global economic power when compared to the total revenue of all governments and all NGOs, businesses have a disproportionate ability to address these problems (World Economic Forum, 2016).

Following the creation of the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) in 2015, the world has witnessed the emergence of movements that call for businesses to take a more active role in shaping social, environmental, and economic outcomes. For too long, proponents of these various movements say, businesses have not been held accountable for the externalities they create and the power they hold in not only minimizing their own negative impacts, but their power to solve problems that NGOs and governments have struggled to adequately address. Up until the beginning of this modern paradigm shift, companies have been widely accepted to only be accountable to shareholders, and their sole imperative was to create value in the form of profits for their shareholders. Today, social movements, such as the B Corp Movement and the Human Rights Movement, are arising that challenge this norm. The backbone of such movements is the idea that companies should create value not only for their shareholders, but for a broader spectrum of parties affected by companies called stakeholders. In this context, the term “stakeholder” refers to any party affected by the company in question, including but not limited to suppliers, customers, employees, the environment, communities, society, and shareholders.

This paper will focus on one of the aforementioned movements – the B Corp Movement – that was created specifically to bring about stakeholder capitalism. The beginning of the B Corp Movement began on July 5th, 2006 with the formation of the non-profit, B Lab, which is responsible for the administration of the B Corp Certification, a certification designed to verify that a company truly creates value for all stakeholders and lives up to its stated mission and values. Companies seeking B Corp Certification must complete the B Impact Assessment (referred to throughout this paper as the assessment), a tool designed to assess the impact of a company holistically based on five categories: Governance, Workers, Environment, Customers, and Community. Companies pursuing B Corp Certification must achieve a score of 80 points or higher on the assessment to obtain certification, with the maximum points obtainable in the assessment being 200. In addition to reaching the 80 point threshold on the assessment, certifying companies must also become a Benefit Corporation. Benefit Corporation legislation brought forth by B Lab created a legal framework (in the states and countries that have approved this legislation) that enables mission-driven companies to remain mission-driven through changes in leadership and ownership, as well as capital raises, by incorporating values and mission into the companies’ foundational governing documents as well as including legal language that protects companies in the event that they should take an action that prioritizes the needs of other stakeholders above those of shareholders (Rawhouser, 2015). In order to remain certified, B Corps are also required to pay an annual fee to B Lab based on sales, publicly publish annual impact reports, and recertify every three years.

As will be discussed later in this paper, certifying as a B Corp poses a number of direct benefits to companies including distinguishment from businesses employing ‘greenwashing’ practices, the solidification of mission and values in the company, and heightened attractiveness to customers and employees, among many others. As many companies came to recognize these benefits, by 2014 the number of Certified B Corps surpassed 1,000 (Gehman, 2017). Today, there are over 6,500 B Corps across more than 70 countries and 150 industries (B Lab, 2023). In fact, as can be seen in Figure 1.1, the B Corp Movement is growing at a pace resembling that of an exponential curve.

Figure 1.1: Count of Certified B Corporations Worldwide, 2007-2016 (Cao, 2017)

As a passionate social entrepreneur, I have a vested interest in the growth of social innovation ecosystems, with the B Corp Certification being a key component of the advancement of stakeholder value creation. During my time as a Peer Mentor at the University of New Hampshire’s B Impact Clinic, a student-run group in which students serve as consultants with the primary duty of helping client companies gain points on the B Impact Assessment, I became invested in understanding what factors contribute to, or inhibit, the growth of the B Corp Movement, a movement I had personally witnessed have a profoundly positive impact on many organizations and their stakeholders. This paper was written to assess which factors drive the growth of the B Corp Movement – defined as the emergence of Certified B Corps and the ecosystem that supports it – and which factors suppress the movement from growing further. Research on this topic may be of use to B Lab in that it will identify areas in which to continue fostering growth and improvement areas that could enhance the adoption of the B Corp Certification. The contents of this paper also serve to contribute to the greater body of research by adding to the relatively small collection of research that exists on B Corps and the B Corp Movement, as well as by providing insights into the broader trend of the increasing prevalence of social enterprises and the unique resources, such as the B Corp Certification, that have facilitated the strengthening of this trend. More broadly, this research is of interest to the entire ecosystem invested in stakeholder capitalism: the idea that our capitalist systems should consciously incentivize companies to provide value to all stakeholders.

WHY CERTIFY?

In order to best understand how the B Corp Movement has grown over time, and to establish a baseline knowledge of the movement, this paper will begin with an exploration of what benefits companies are pursuing when they seek certification. On B Lab’s website, the intended benefits are identified as demonstrating high social and environmental performance, making a legal commitment for accountability to all stakeholders (through incorporation as a Benefit Corp, a required part of the certification process), and exhibiting transparency by displaying performance on the B Impact Assessment on the B Lab website and the certified company’s website (B Lab, 2023). B Lab further elaborates on numerous benefits that B Corp Certified companies experience in the B Corp Handbook; among the benefits stated include lower churn and cost of acquisition as well as higher retention rates for employees and customers, attraction of value-aligned investors and suppliers, and increased competitiveness of job applications which leads to improved quality of accepted candidates (Honeyman, 2019).

One benefit of B Corp Certification frequently highlighted in the literature is the avoidance of ‘mission drift,’ defined as the failure to holistically honor two or more conflicting missions, such as the mission to maximize profits and a socially or environmentally centered mission (Park, 2018; Moroz, 2021). The certification process accomplishes this result by requiring incorporation as a Benefit Corp or, in the case of LLC’s and other non-corporate for-profits, institutionalization of similar ‘mission lock’ clauses into the company’s governing documents. This change solidifies a company’s mission statement and commitment to all stakeholders into the certified company’s fundamental governance structure, in effect forcing the company to reconcile and actively manage any discrepancies between its mission to create profits and its more altruistic mission(s) to benefit its non-shareholder stakeholders. In addition, the B Corp Certification process itself requires that companies institutionalize positive practices, such as the measurement of social and environmental impact or regular performance reviews with employees, that may have previously been unspoken norms. By solidifying these policies and procedures, certified companies are far more likely to retain such practices that value all stakeholders through events such as changes in ownership, macroeconomic downturns, and changes to the leadership team (Park, 2018). With improved odds of retaining positive practices, Park suggests that B Corps are enabled to make long-term commitments to social and economic good that are perceived as exceptionally credible (2018).

Non-certified and B Corp Certified companies alike use the assessment to benchmark social and environmental performance, and to expand policies and procedures as the organizations’ maturities evolve. Despite the evolution of Environmental, Social, Governance (ESG) and other methods of measuring social/environmental performance, there are few comprehensive resources for companies to measure qualitative aspects of these performance areas and benchmark continual improvement over time (Grimes, 2018). This is especially the case for small to medium enterprises (SMEs), which may struggle to quantify the impact of their practices for lack of financial means to acquire the appropriate measurement tools. In contrast with purely quantitatively driven approaches to measuring social/environmental impact, such as ESG, the assessment assigns a quantitative value to qualitative factors. For example, a company seeking certification may obtain points on the assessment for having certain policies or procedures present in their employee handbook, whereas such qualitative factors are unlikely to be accounted for when using a purely quantitatively driven method of performance measurement. Due in part to these advantages of use, since the assessment was launched in 2007, over 60,000 businesses have registered to use the assessment (Muiru, 2019).

Based on the literature, becoming certified as a B Corp poses a number of reputational benefits. One of the baseline benefits of the certification is the role it plays in distinguishing certified companies’ impacts from greenwashing, the practice of a company marketing itself as ‘green’ and ‘good’ when in reality, the magnitude of the company’s impact is far less than its stated positive impact (Cao, 2017). By certifying as a B Corp, businesses are vetted by B Lab and evaluated using rigorous sustainability standards. Consumers who see the B Corp label on products can thus be assured that the company they are purchasing from is not only appearing sustainable, but also operating in a sustainable manner. Kim suggests that the current business environment is, “in the midst of a ‘greenwash’ revolution” and that the B Corp Certification “helps consumers sort through the marketing hype to find businesses and products that are truly socially and environmentally responsible (2017).” Kim further concludes that a key driver of the B Corp Movement’s growth is the recognition of the PR benefits to appearing sustainable and the increasing efforts of for-profit companies to be perceived as “green and good (2017).”

Evidence suggests that the B Corp Certification might offer businesses more than simply the reassurance of their stakeholders that they are not greenwashing. The certification may also serve as a differentiator for businesses that achieve it, particularly in industries where competitors have well-defined CSR and sustainability practices. In fact, Kim identified a correlation between the prevalence of CSR in an industry and the emergence of new B Corps in the industry (2017). SMEs, in particular, often struggle to differentiate themselves against larger incumbent competitors with well-known and well-established sustainability programs. The B Corp Certification offers SMEs an advantage in that they can use the certification as proof of their embodiment of environmental and social responsibility, a stamp of approval that their larger counterparts experience greater difficulty in obtaining (Park, 2018). By providing this proof, social enterprises can build trust with stakeholders. Trust built on the basis of strong social and environmental responsibility may have financial benefits too; research by Woulfe and Sifre found that almost 70% of millennials would pay more for products sold by socially and environmentally responsible brands (2015). Park suggests that achievement of the B Corp Certification is not only valuable for companies selling to end-consumers; the certification can also attract B2B customers because “entrepreneurs like to work with like-minded clients who share the same values (2018).”

The B Corp Certification can help certifying companies define their individual identities. Grimes finds that the greater the extent that entrepreneurs “perceive ESG-related values as central and distinctive to their identities,” the greater the desirability of related certifications becomes to these entrepreneurs, because such certifications validate the entrepreneur’s alignment with those values (2018). Grimes maintains that while both the legitimacy deficit explanation (certifying as proof of not greenwashing) of why companies pursue certification and the identity-work perspective are generally plausible, the identity-work perspective is more feasible given that if companies primarily sought B Corp Certification to overcome legitimacy deficiencies, they would be expected to pursue certifications that are widely adopted and under-scrutinized in that there are few penalties associated with inauthentic certification (2018). While the B Corp Certification is growing in adoption and awareness of the certification is increasing, it is by no means common in today’s business environment. Grimes’ argument posits that in addition, if companies adopt sustainability certifications primarily as promotional tools, they are frequently subject to “increased scrutiny and skepticism (2018).”

According to some academic research, as a result of their adoption of sustainable practices, B Corps can experience greater long-term profitability and higher valuation premiums compared to competitors. Gazzola found that companies identified as sustainable when compared to competitors in the industry saw less volatility in their stock prices, as well as finding a statistically significant correlation between net income and point values in the environment, customers, and workers sections of the assessment (2019). Gazzola attributed the correlation between the above sections of the assessment and net income to the intangible benefits obtained by adopting the stakeholder-based practices necessary to become B Corp Certified, such as ease of attracting high-quality human capital and strong customer retention rates (2019). Chen found that from 2007 to 2011 (the length of the study), B Corps financially outperformed their public company industry competitors, both large and small (2014). Chen did, however, find no correlation between B Corps’ revenue generation and productivity and their score on the assessment, except for the year 2011, which was the final year of the study (2014). Ultimately demonstrating the link between sustainable practices and long-term valuation appreciation, a team of Harvard researchers completed a detailed quantitative analysis that showed that by investing a dollar on a highly sustainable company in 1993, a portfolio of about $23 is reached after a decade, as opposed to a portfolio of $15 when selecting comparable low-sustainability companies (Eccles, 2014). One meta-study found that “the relationship between socially responsible business practices and financial performance was positive in 27% of the 167 studies examined, not statistically significant in 58% of the studies, and negative in just 2% of the studies (Sneirson, 2009).” Many proponents of stakeholder capitalism argue that not only are sustainable practices beneficial to the environment and other stakeholders, but also to shareholders holding investments with long time horizons. As will be discussed later, short-termism can be a significant headwind to the adoption of the B Corp Certification and practices associated with stakeholder capitalism, due to the main financial benefits of sustainable practices being realized in the long-term.

According to Grimes, all certifications face a chicken and egg dilemma (2018). For companies to seek a given certification, the certification must be perceived as valuable. However, the ultimate goal of certifications is to become adopted, and as more companies adopt a given certification, they dilute the certification’s perceived value. Due to this dilemma, early-stage certifications frequently struggle to grow in prevalence. Grimes further posits that, “while traditional and widely accepted certifications are adopted due to a need for conformity and legitimacy, early-stage certifications are adopted due to a need for authenticity (2018).” Since the B Corp Certification is a rapidly evolving, relatively unestablished early-stage certification, these suggestions support the theory that companies adopt the B Corp Certification not to overcome a legitimacy deficit but to affirm socially and environmentally aligned identities. However, if the aforementioned pattern follows, as the B Corp Certification continues to grow in prevalence, an increasing number of businesses will seek the certification as a means of conformity with social and environmental performance expectations rather than as a form of differentiation.

INDIVIDUAL AND ORGANIZATIONAL CONSIDERATIONS

After discussing the advantages and disadvantages the B Corp Certification offers to businesses that achieve it, it would follow that the way the decision is made to certify, or decertify, at the individual and organizational levels should be analyzed. An overarching theme across the literature is that the decision to certify or decertify is predominantly top-down leadership-driven (Martin, 2020; Rawhouser, 2015). One of the most common scenarios in which a business pursues B Corp Certification is the case in which the entrepreneur wants to leave an imprint on the organization they founded and becomes attracted to the B Corp Certification and incorporation as a Benefit Corp for their potential to institutionalize and therefore immortalize the founding principles, mission, and values (Rawhouser, 2015). As a required component of obtaining the B Corp Certification, companies must also become a Benefit Corp or (incorporate comparable clauses that protect stakeholder value creation, in cases where incorporation as a Benefit Corp is not possible), which not only solidifies a company’s mission in its governing documents, but also theoretically protects management from discourse in the event that enforcement of the company’s stated mission conflicts with shareholder value maximization. Not only does this help the founder(s) of a business retain control during their tenure, but it also ensures that important aspects of their vision for their company will continue to be implemented beyond their tenure.

B Corp Certification has been disproportionately adopted by women-owned businesses, with one study finding that women-owned businesses are 3.65 times more likely to become B Corp Certified than otherwise identical non-women owned industry counterparts (Grimes, 2018). The study found that women-owned businesses were especially likely to obtain B Corp Certification when they fell within region-industry contexts where sustainability norms are weaker, mimetic pressure to become a B Corp is lower, and women-owned businesses are less prevalent (Grimes, 2018). In fact, Grimes found that for all businesses, propensity to become B Corp Certified was higher in contexts where sustainability norms are weak (2018). In support of this conclusion, Kim’s research found that extreme profit-maximizing business conduct in an industry, such as mass layoffs or hostile takeovers, is predictive of B Corp emergence in that industry (2017). These findings may support the identity-work theory of why businesses pursue certification, given that propensity for women-owned businesses to obtain certification is higher in contexts where many of the defining features of these social ventures, such as an emphasis on sustainability, would be considered abnormal, or rare. In these contexts, B Corp Certification serves as a differentiator, rather than as a means of conformity to pre-existing norms within the companies’ regions or industries. However, some researchers believe women social entrepreneurs may pursue certification to overcome discriminatory legitimacy discounts associated with negative gender stereotypes, patriarchy, and institutionalized gender segregation (Thébaud, 2015; Zhao and Wry, 2016). Further examining the impact of stereotypes on the decision of women-owned businesses to pursue B Corp Certification, many studies have identified widely held stereotypes that women more strongly adopt and embody sustainability and ESG-related values, making it unlikely that women-owned businesses would pursue B Corp Certification to overcome a legitimacy deficit with respect to embodiment of sustainability (Baltes, 2010; Hyde, 2021; Koenig, 2014). Grimes’ findings concluded that women entrepreneurs have been crucial early adopters of the B Corp Certification, and that their adoption and championing of the certification has helped build up the significant legitimacy that the certification holds today (2018).

Many socially responsible companies ingrained in the Business and Human Rights (BHR) Movement disapprove of the B Corp Certification because it is possible for companies operating without proper human rights due diligence or violating human rights to become B Corp Certified. While the assessment encourages the use of social impact assessments as a method of assessing impact on communities, the BHR Movement vehemently argues that human rights impact assessments (HRIAs) should be employed within the assessment as HRIAs adhere to the entire scope of international human rights law (Bauer, 2015). The main differences between HRIAs and social impact assessments are that HRIAs are framed by the International Bill of Rights while social impact assessments are not, and that HRIAs consider how an organization could possibly interact with each and every right identified by the United Nations as a Basic Human Right while social impact assessments focus more narrowly on an organization’s direct impacts to individuals or communities (Bauer, 2015). The broad scope and international legal compliancy of HRIAs makes them a generally more comprehensive choice with respect to human rights due diligence. The assessment does include a disclosure questionnaire and many of the questions within this questionnaire are closely related to BHR content, and although the disclosure questionnaire is unweighted in terms of the point value answers add or detract from a company’s score on the assessment, companies can be disqualified from B Corp Certification based on their answers to disclosure questions. However, BHR advocates argue that the disclosure questionnaire’s focus on company procedures, rather than actual impact, allows businesses to be assessed based on stated processes when their impact on human rights may still be severely negative (Bauer, 2015). The structure of the assessment being incapable of assessing and verifying true impact on human rights as well as being nonconforming to international human rights laws gives rise to objections to the B Corp Certification from the BHR community.

Figure 1.2: US-based B Corp Decertification Rates Between 2007 to 2020 (Martin, 2020)

The average attrition rate for the B Corp Certification since its inception is approximately 33% to 34%, according to multiple academic studies (Cao, 2017; Martin, 2020). As can be seen on Figure 1.2, the attrition rate has been drastically declining since 2012, with academically published records of the number of decertifying organizations being nonexistent after the 2018. Martin found the certification’s attrition rate to be higher in small businesses, with SMEs particularly citing difficulty in extracting tangible extrinsic benefits from certification and a lack of support from B Lab and the greater B Corp ecosystem (2020). For example, B Corp Certified law firms frequently complained about B Corps expecting free legal services from them, while some companies stated that they had become disillusioned by how “detached and bureaucratic” B Lab had become in its administration and leadership of the B Corp community (Martin, 2020). Other firms were less focused on the extrinsic benefits of the certification, stating that they decertified because they believed that their missions could be achieved without being affiliated with B Lab (Cao, 2017). Some companies stated that they decertified due to the recertification process, which is required every three years, being “highly cumbersome, complicated, and time consuming (Martin, 2020).” Many companies believed the certification process was too easy, witnessing companies they believed did not have a true commitment to stakeholder value creation obtaining certification; others believed that the certification process was far too difficult and expensive to justify the benefits, which are hard to quantify (Martin, 2020). These conflicting accounts display the aforementioned dilemma early-stage certifications face in that they must attempt to build legitimacy for the certification by growing adoption, but also must retain the prestige of the certification by making it difficult to obtain and being selective in awarding certification. As shown in the results of Cao and Martin’s studies, this dynamic in early-stage certifications has led to some dissatisfaction with the B Corp Certification on both ends of the perceived difficulty spectrum, though the decertification rate is notably decreasing year-over-year, which may reflect the maturing of the certification. The vast variety and contradictory nature of decertifying companies’ complaints suggests that many decertifications may be due in part to inaccurate expectations company leadership may have had about the B Corp Certification’s benefits, and furthermore, B Lab’s mismanagement of said expectations.

Lack of succession planning or loss of a “certification champion,” whether through M&A of the certified company, changes in management, or changes in shareholders, were cited as among the most common causes of decertification across the academic literature examining B Corp decertifications (Cao, 2017; Martin, 2020). While the new controlling or operating parties in each case illustrated a situationally unique motive for decertification, a common motivation was renewed commitment to maximizing shareholder value and a preoccupation with short-term financial results – an operational philosophy that several academics have argued leads companies to under-invest in long-term growth and sustainability (Farley, 2013; Lazonick, 2009; Pearlstein, 2014; Stout, 2018). In fact, McKinsey found that 55% of CFOs said they would forgo a positive investment if it meant marginally missing quarterly earnings targets (2013). Given the established link between corporate sustainability and long-term profitability, but not necessarily short-term profitability, a strong focus on short-term profits could easily prevent management teams from recognizing the value in adopting socially and environmentally responsible practices and by extension, prevent management from pursuing certifications, such as the B Corp Certification, that requires such practices to be instituted. As will be discussed later, economic incentive structures in today’s markets – particularly the public markets – encourage such mindsets centralizing around short-term profitability, further constraining the B Corp Movement’s growth. Despite the prevalence of these short-term focused strategies and their demonstrated ability to shift organizations away from sustainable practices and B Corp Certification, Martin’s study generally attributed decertification not to abandonment of company missions, but to a diminishment in perceived value of the B Corp Certification, except in cases of M&A (2020).

CHALLENGES AND OPPORTUNITIES FOR SOCIAL VENTURE STARTUPS

As the B Corp Certification was designed to lend legitimacy to true social ventures, it would follow that factors governing the emergence of new social ventures would be of importance when holistically analyzing the growth of the B Corp Movement. When considering social venture startups as a crucial component of the certification’s demand-side growth, a number of challenges and opportunities specific to social venture startups become relevant to the growth of the B Corp Movement as a whole. As the B Corp Certification stands today, because the assessment focuses on processes and procedures, with some of the highest point value policies being quite expensive to institute (such as exceptional healthcare benefits), businesses must achieve a significant degree of organizational maturity to reasonably expect to cross the 80 point threshold to become B Corp Certified. This poses a barrier to entry for new ventures pursuing immediate certification. The annual dues associated with B Corp Certification, as illustrated in Figure 1.3, can also pose a financial barrier to entry for new ventures, which have unreliable or nonexistent cash flows. In an attempt to keep early-stage startups engaged with the movement, B Lab created the Pending B Corps Program, which helps startups gain a head start on the full B Corp Certification process and signal to their stakeholders that they are value-aligned with and are actively pursuing the certification (B Lab, 2023). Becoming a Pending B Corp is a temporary status that expires after a predetermined period of time set by B Lab, incentivizing startups to eventually go through the more rigorous B Corp Certification process. To become a Pending B Corp, startups must complete the legal requirements associated with B Corp Certification (becoming a Benefit Corp or non-corporate equivalent), submit a prospective assessment that will not go through the verification process as a traditional B Corp Certification submission would, and pay a small one-time fee determined by the startup’s local B Lab organization (B Lab, 2023).

Figure 1.3: B Lab Fee Schedule (B Lab, 2023)

In addition to the barriers startups face in obtaining certification, the unique challenges new social ventures face in growing to the point where certification is a feasible possibility affect the growth of the B Corp Movement as a whole. Thompson found that social ventures tend to struggle to find early-stage funding from angel investors and venture capitalists, even in geographic regions and industries that traditionally have a strong venture capital industry (2018). B Lab states in the B Corp Handbook that B Corps and Benefit Corporations do not struggle more than traditional ventures in raising investment capital, even citing an example in which Danone, a publicly traded Certified B Corp, was able to negotiate a lower cost of capital from several major banks due to its achieving the B Corp Certification (Honeyman, 2019). This does not directly contradict Thompson’s findings, as Thompson found that achieving B Corp Certification increased the odds of obtaining startup funding from impact investors – investors focused on investing in social ventures that garner profits while also making a positive social or environmental impact (2018). However, prospective B Corp startups and B Corp Certified companies alike would fall under the category of social ventures, and as such, should experience similar challenges and opportunities when seeking financing, regardless of what those challenges and opportunities may be. Despite B Lab stating that B Corps and Benefit Corps do not experience challenges in raising capital, this is a challenge consistently cited by social entrepreneurs in Thompson’s study (2018). Some social entrepreneurs in the study believed their struggles in maintaining investor interest were derived from the lack of famous or extraordinary social venture liquidity events that could reference to generate interest in social ventures more broadly (Thompson, 2018).

However, one of the most consistent inhibitors of investor interest cited by social entrepreneurs was the inability of investors to distinguish between social ventures and nonprofits, with many investors becoming disillusioned with social ventures due to their dual pursuit of both impact and profits (Thompson, 2018). Often, social entrepreneurs will heavily emphasize the impact potential of their venture, giving off the impression that (whether true or not) the entrepreneur will prioritize their mission for impact over their mission for profits, therefore degrading the perceived upside potential of the investment opportunity and investors’ trust that the entrepreneur has the investors’ best interests in mind. By contributing to the formation of a new organizational category and identity, the B Corp Certification and the Pending B Corp designation for startups specifically, combats this issue by making it easier for investors and other stakeholders to understand what the company inherently is and does the same way they understand a nonprofit or a corporation (Grimes, 2018).

Legal structures (such as the Benefit Corporation structure) that are tailored to the needs of social ventures, as well as specialized legal help for establishing and maintaining these corporate structures, were also found to be key growth drivers for social ventures, as not only do these structures protect management from shareholder primacy and immortalize the company mission through capital raises and changes of ownership, but they also lend legitimacy to the social enterprises’ fusion of impact and profitability under one organizational structure (Thompson, 2018). A study by Rawhouser explored factors that make a state or country more or less likely to adopt Benefit Corporation legislation, with the study finding the adoption of Benefit Corporation legislation positively correlated with tax attractiveness, green economic activity, Democratic party control, and greater levels of legislative activity and activism in the state or country (2015). The study also found that greater levels of nonprofit activity in a state or country was negatively correlated with adoption of Benefit Corporation legislation, with Rawhouser attributing this to notable resistance of nonprofits to the existence of Benefit Corps (2015). Surveyed nonprofit managers stated that the emergence of Benefit Corps may threaten the nonprofit category, citing that it is difficult for a nonprofit to transition to a for-profit entity and that with nonprofit organizations being heavily dependent on donor dollars, they fear that prospective donors would prefer to invest in Benefit Corps that are designed to make a positive impact while also yielding a return on investment for donors (Rawhouser, 2015).

Other identified drivers of growth in the number of social ventures are infrastructural in nature, such as the existence and prevalence of impact angel groups, social venture accelerators, and social venture entrepreneurship competitions in developing social innovation ecosystems (Thompson, 2018). Education on impact investing was another key growth driver of social innovation ecosystems, as with more education on impact investing comes a greater availability of investment capital seeking to be allocated to social ventures (Thompson, 2018). The expanding saturation of ESG assets and methodologies is having a profound impact on awareness and industry knowledge of impact investing. In recognition of the importance of impact investing to the B Corp Movement, B Lab created the Global Impact Investing Rating System (GIIRS) which uses assessment results from portfolio companies to measure the impact of an impact investment portfolio (B Lab, 2023). According to Muiru, GIIRS “makes it easier for impact investors to measure impact, and thus encourages entry into this investment category, improving access to capital for B Corps and finally, encouraging B Corp Certification as a result (2019). There are over 100 GIIRS-rated impact investment funds managing upwards of $1.5 billion in assets under management, with each of these funds being likely to prefer B Corps to non-B Corps, further encouraging certification (Grimes, 2018; Muiru, 2019).

Based on the academic literature, bottom-up approaches to building social venture ecosystems are generally more successful at producing ecosystems that scale than top-down attempts to replicate existing examples such as Silicon Valley, because formation of entrepreneurial ecosystems is primarily driven by social interactions between individuals, and because with a bottom-up approach, the ecosystem has the appropriate infrastructure for its stage of development (Dorado, 2005; Furnari, 2014; Thompson, 2018). In early-stage social venture ecosystems specifically, Thompson cited “new terminology, the use of social media to attract like-minded individuals, the creation of dedicated physical [work]space, the development of new legal forms of organization and legal practices, and the establishment of new resource pools and methods for funding social impact businesses” as key developments that supported the growth of social innovation ecosystems (2018). B Lab appears to have employed a bottom-up approach in facilitating the growth of the B Corp ecosystem by creating the B Hive, a network designed to connect social entrepreneurs, who often go on to partner, patronize each other’s businesses, serve as mentors to one another, among many other ways entrepreneurs collaborate (B Lab, 2023). Not only does the B Hive serve to improve B Corps’ sustainability practices by providing opportunities for B Corps to collaborate towards common outcomes, with social interaction opportunities being a key driver of the creation and growth of social venture ecosystems, but it also aligns with the bottom-up ecosystem growth approach as the B Hive provides an environment for partnerships to organically form without investing in expensive infrastructure that may be premature for the size and complexity of the community.

CHALLENGES OF CERTIFYING PUBLIC & MULTINATIONAL CORPORATIONS

Publicly traded multinational corporations have the unique ability to move markets and make strides to change the culture of the overarching business environment using their large budgets, extensive workforces, and wide exposure to audiences across the globe. However, these entities face perhaps more challenges than any other for-profit organizations in obtaining the B Corp Certification, due to characteristics inherent to the certification and the global financial markets, as well as the cultural expectations of managers to maximize profits. If large publicly traded companies face incredible difficulty in adopting the B Corp Certification, this is a significant constraint on the scalability of the movement, as these organizations hold far more power than small to medium sized businesses (or even large private companies) in making the infrastructural and systemic changes necessary to realize the ultimate vision of a sustainable and equitable future that B Lab is trying to accomplish.

Among the most significant challenges to public multinationals pertains to the assessment being far better suited for SMEs than for larger companies that may have slow and bureaucratic approaches to embracing the drastic changes necessary to become B Corps. The larger an organization is, the more heavily ingrained its procedures, processes, culture, and practices are, further compounding this challenge. The assessment has an inherently complex approach to encouraging sustainable and equitable practices across all facets of a business, but public multinationals also have inherent complexities that make navigating the assessment even more demanding than it is for SMEs, such as their multiple subsidiaries, highly sophisticated corporate structures, diverse product lines and customer segments, and exposure to various regions across the globe with varying laws and cultural norms (Stubbs, 2017). Furthermore, public multinationals’ tendency to have diverse product lines that span industries make them more vulnerable to disqualification from eligibility for B Corp Certification, as organizations of this size are disqualified for having greater than 1% revenue exposure to any of the following industries without a formal commitment to exit those industries: tobacco, firearms, weapons or munitions, coal, pornography, and casinos (B Lab, 2023). Additionally, as the vast majority of publicly traded multinationals are C Corps, the B Impact Assessment would require conversion to a Benefit Corporation, which is extremely complicated for sizable organizations with complex legal structures (B Lab, 2023). While there have been a few companies that were structured as Benefit Corporations prior to their Initial Public Offering (IPO), as of 2020, the feat of becoming a Benefit Corp while already publicly traded has never been accomplished (Martin, 2020). Additionally, there is significant pushback from supporters of the B Corp Movement on involving public and multinational corporations, as many of these supporters feel as though large corporations inherently cannot achieve the social and environmental performance standards that traditional B Corps can, and that by extension, bringing these corporations on board would dilute the movement (Marquis, 2020).

B Lab has established two “large enterprises pathways,” which are intended for eligible private or publicly traded companies with $100 million to $999 million in annual revenue, and with 10 or more subsidiaries operating in multiple countries, as well as companies with over $1 billion in annual revenue, which have to abide by additional criteria (B Lab, 2023). The first large enterprise pathway involves certifying the parent company as a B Corp. In this pathway, the parent company may certify by fulfilling the performance and legal requirements for over 95% of operations, while maintaining full transparency (B Lab, 2023). This approach requires less visibility and participation from subsidiaries but is considerably more resource-intensive and involves more upfront costs than the second large enterprise pathway (B Lab, 2023). The second large enterprise pathway involves each subsidiary independently meeting the B Corp Certification requirements. This approach is less resource-intensive for the parent company, garners a more organic process of building buy-in and momentum, and makes meeting the legal requirements an easier feat for the subsidiaries (B Lab, 2023). However, depending on the organization, this method can be more expensive over time and may not be possible for businesses with more centralized corporate structures (B Lab, 2023). Companies with over $5 billion in annual revenue must choose from one of the two large enterprise pathways, but these organizations must also participate in B Lab’s B Movement Builders program (B Lab, 2023). The B Movement Builders program was created in recognition of large multinational corporations’ ability to move markets and alter the overarching culture of the business environment. The program is designed to help participating companies “make credible commitments, identify opportunities for scalable collaboration, and work internally to affect impactful transformation that accelerates a global systems change of business and culture (B Lab, 2023).” B Lab has also created a multi-stakeholder advisory board, called the Multinationals and Public Markets Advisory Council (MPMAC), to solicit feedback and recommendations to B Lab on how to best enable large multinational and public companies to participate in the B Corp Movement (KKS Advisors, 2017). In recognition of the importance of impact investing to the growth of public and multinational B Corps, through MPMAC, B Lab is engaging with large institutional investors such as BlackRock, CalPERS, and Morgan Stanley, to collaborate on expanding industry knowledge on impact investing and on the implications of the Benefit Corp structure and the B Corp Certification (KKS Advisors, 2017).

A key challenge that plagues publicly traded companies seeking B Corp Certification is the public markets’ inherent focus on maximizing short-term profitability and shareholder returns. This imperative directly conflicts with the long-term stakeholder value creation strategy promoted by the B Corp Certification which, as discussed earlier in the paper, the academic literature generally agrees maximizes shareholder returns and profitability in the long-term. The public markets’ focus on short-term profitability has been reinforced by a longstanding cultural norm in the broad business environment that is predicated on the misconception that maximizing shareholder value is legally required of businesses, as well as short-term oriented economic incentives. Despite the overwhelming body of research demonstrating that shareholder value maximization is not legally required of businesses, this assumption has been baked into expectations for corporate managers and the incentives that influence their decisions (Park, 2018; Sneirson, 2009). For example, if corporate managers are successful in significantly increasing their firm’s stock price and therefore shareholder wealth, they are more likely to keep their jobs, get raises and promotions, and reap more informal rewards such as recognition in the workplace and the feeling of a job well-done (Sneirson, 2009). To align employees’ economic incentives with those of shareholders, firms often offer stocks and stock options as part of compensation packages. With these economic incentives aligned, the public markets directly encourage corporate fiduciaries to maximize company share price and therefore, their own compensations (Sneirson, 2009). With such powerful expectations, further reinforced by economic incentives, executives believe shareholder value maximization is a core purpose of their jobs. In conjunction with the financial markets, most for-profit companies measure financial performance on a quarterly basis, meaning that employees’ ability to operate the organization is based on how the business performs in the short-term. The measurement of performance in the short-term therefore leads to decisions being made based on their short-term results, thus solidifying the organization’s focus of short-term shareholder value maximization (Marginson, 2009). By granting points on the assessment for measuring customer satisfaction, employee satisfaction, product quality and other measures of corporate success, the B Corp Certification aligns with the prominent suggestion within academia to address the issue of short-termism: institute measurement of non-financial measures that better reflect long-term performance (Lambert, 1998; Sliwka, 2007).

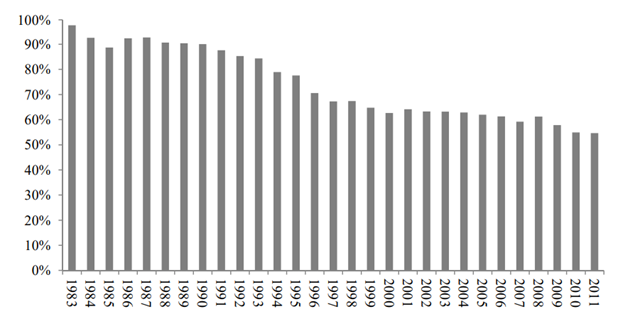

The issuance of dividends is another incentive that has traditionally aligned investors with long-term value creation. Without dividends, the only way to make returns on stocks are to rely on capital gains, which tend to be much more volatile and event-driven than dividends. The more investors that buy and sell stocks in the short-term, the more volatile stock prices become, further incentivizing short-term investing strategies that exploit volatility. This relationship has been well-documented in multiple studies that conclude that companies that do not offer dividends have significantly more volatile share prices than those that do offer dividends (Baskin, 1989; Johnson, 2009). As can be seen on Figure 1.4, less companies are offering dividends today than ever before. Konieczka’s sample of over 2,000 companies with market capitalizations above $100 million and net profits above $10 million traded on the AMEX, NASDAQ, and NYSE stock exchanges saw 98% of companies offering dividends in 1983 and only 55% offering dividends in 2011 (2014). This underpins an increasingly volatile market environment, making conditions ideal for short-term trading and therefore suppressing the likelihood that public companies will be valued based on long-term stakeholder value creation. The predominance of economic incentives focusing public companies on short-term profitability is a significant headwind for the B Corp Movement, as these companies have the most power to make the systemic and cultural changes necessary to accelerate the movement but are the least incentivized to make such changes.

Figure 1.4: Percentage of Companies Paying Dividends Over Time (Konieczka, 2014)

Companies that have IPOed with only B Corp status and not incorporation as a Benefit Corp have experienced significant attacks, such as hostile takeovers, on their social and environmental practices, with these attacks driven primarily by short-termism in the public markets (Park, 2018). Social ventures have proven more resilient towards these risks than companies that do not have social and environmental performance built into their core business models, as it is difficult to separate these core competencies from, for example, a clean energy company, than it is to separate them from a more traditional company that donates money to charity (KKS Advisors, 2017). It is notable that despite posing higher barriers to entry to becoming a Certified B Corp, B Lab's recent decision to require Certified B Corps to register as Benefit Corporations is likely to facilitate greater protection for public companies seeking to maintain their social and environmental practices and values, and may thus spur greater adoption and greater success rates of B Corp Certification among public companies (KKS Advisors, 2017).

QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW METHOD

As a core component of this paper’s research into the growth drivers and inhibitors of the B Corp Movement, we conducted interviews with five founders, CEOs, and executives at companies that are actively pursuing B Corp Certification as well as another five such professionals from companies that have already become Certified B Corps. Within the sampled company, obtaining a suitable diversity of company size, industry, and length of certification status was prioritized. While this diversity was largely successfully executed upon, the sample does have some limitations. The sample did not include representatives from any publicly traded companies due to confidentiality and materiality issues arising from there being only approximately 30 publicly traded Certified B Corps (B Lab, 2023). However, representatives from the privately held companies interviewed were asked to provide their perspectives on how they believe becoming a publicly traded company might affect their ability to be achieve or maintain B Corp Certification and their ability to effectively further their missions. Another limitation of this sample is that due to immense difficulty locating and obtaining responses from executives representative of companies that chose to decertify after previously achieving B Corp Certification, these companies were not represented in the sample of interviewees.

These in-depth interviews were approximately 30 minutes long, with the questions designed to address common themes that arose in the literature review such as identity theory, the importance of social venture ecosystems, and the advantages and disadvantages of becoming certified. During these interviews, participants were asked open-ended questions about their reasons for joining the B Corp Movement, the role that B Lab plays in accelerating the movement, how the certification process could be improved, the reactions of their investors to their pursuit of B Corp Certification, their perspectives on the mission lock (Benefit Incorporation or other legal equivalent) requirement, and how the certification has affected their views on the company’s overall identity (the qualitative interview guide can be found in Appendix A). After the interviews were completed, records of interviewee responses were analyzed for common themes to develop insights into the broader sentiment surrounding the B Corp Certification and many of the aforementioned factors related to the growth of the B Corp Movement.

QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW FINDINGS

Across the literature, avoiding mission drift by becoming a Benefit Corp (or other legal equivalent) and by institutionalizing sustainable and socially responsible business practices was generally identified as a key motivator for adoption of the B Corp Certification (Farly, 2013; Lazonick, 2009; Martin, 2020; Pearlstein, 2014; Rawhouser, 2015; Stout, 2018). When executive respondents were asked about the main reasons for their pursuit of certification and about how they required the requirement to become a Benefit Corp (or other legal equivalent) to become a Certified B Corp, the vast majority of respondents cited the fear of a change of control in their companies being a catalyst for mission drift as being one of their top three motivators for pursuing B Corp Certification. Despite much of the literature suggesting that the mission lock requirement was a significant barrier for companies pursuing certification, only one respondent cited the mission lock as a challenging aspect of the certification process, with all other respondents solely expressing appreciation for the mission lock requirement as a method of securing the long-term survivability of their companies’ missions. Many of these respondents also indicated that the mission lock requirement was not a difficult hurdle in the certification process, as a result of their company’s stakeholders and internal cultures already being value-aligned with such a change.

When executives were asked if becoming publicly traded would affect their companies’ abilities to execute on their missions and values, as well as to retain B Corp Certification, almost all respondents specifically cited a desire not to IPO their companies to avoid what one interviewee described as “aggressive profit-seeking behavior” present in the public markets. This sentiment was even shared across executives representative of companies in such financial standing necessary to properly execute an IPO. This near unanimity in reaction to the idea of becoming publicly traded suggests that not only are there few publicly traded B Corps because of the difficulties that existing publicly traded corporations have in achieving certification, but also because organizations that naturally align with the B Corp Certification consciously avoid the IPO process due to the notoriety of the public markets for focusing on short-term profitability over sustainable and socially responsible business practices. These responses are illustrative of a clear aversion to mission drift, as well as conscious decisions made by interviewed executives to avoid mission drift, thus tangentially supporting the conclusion made by the literature that avoiding mission drift is a key motivator for adopting the B Corp Certification.

Many executives expressed a value of long-term profitability – in large part catalyzed by sustainable and socially responsible business practices – over short-term profitability, demonstrating awareness of the correlation between long-term profitability and factors that serve as key performance indicators in both the B Corp Certification and ESG frameworks, a relationship that is widely accepted across academia and more granularly, across the literature pertaining to Certified B Corps. However, not a single respondent cited the pursuit of greater long-term profitability as a reason for pursuing certification. Some respondents did, however, acknowledge that this was a benefit their companies realized as they navigated the certification process and subsequently became B Corp Certified. These findings suggest that while pursuit of greater long-term profitability may not be a driver for initial adoption of the B Corp Certification, it may be a driver for continued engagement with the certification through recertification and conscious efforts to improve scores on the B Impact Assessment.

Regardless of industry, company size, certification status, or length of certification, three overarching themes emerged as the most consistent reasons why executives chose for their companies to pursue B Corp Certification: using the B Impact Assessment to benchmark impact and as a roadmapping tool, distinguishment from greenwashing, and differentiation in the marketplace. Pertaining to the former, all of the executives from companies not yet certified indicated using the B Impact Assessment as a growth roadmapping tool for improving their businesses’ social and environmental impact across each of their key stakeholder groups. One executive from this subset even indicated that while their company does not anticipate becoming B Corp Certified in the near-term, they use the B Impact Assessment extensively as a tool for improving impact across their operations. With the B Impact Assessment being a free to use, easily accessible online tool, it is possible that the assessment is used by many to gain an initial understanding of the B Corp Movement and to gain immediate value from the certification process, which may often assist companies in deciding whether the B Corp Certification is the right choice for their company. In this sense, the user experience while navigating the B Impact Assessment may be a critical determinant of whether a B Impact Assessment user decides to progress further in the certification process.

In support of the conclusions made by the literature and furthermore, support of the original intent of the B Corp Certification, almost all of the interviewed executives indicated that a core reason for their pursuit of certification was to distinguish themselves from other greenwashing companies in their respective industries and to differentiate themselves in the marketplace. These motivators are closely related in that within many industries, distinguishment from greenwashing companies is a demonstrable differentiation in the marketplace, where it is often difficult to prove the legitimacy of claims made about social and environmental impact. A key example in the literature that illustrates this interconnectedness found that for all businesses, propensity to become B Corp Certified was higher in contexts where sustainability norms are weak (Grimes, 2018). Many executives cited both distinguishment from greenwashing companies and the value-alignment of the certification with their company’s mission as reasons for pursuing the certification, suggesting that these two motivators are not mutually exclusive, as was suggested by Grimes (2018). However, Grimes’ conclusion that the decision to pursue B Corp Certification is predominantly top-down leadership-driven was validated by the qualitative interviews, as all interviewees framed the decision to pursue certification as an idea sourced from top leadership, with the decision also made by top leadership – often with buy-in from other stakeholder groups such as employees and customers (2018).

When asked directly, no currently certified companies cited reasons that they believed would be likely to compel them to decertify. One interviewee stated: “the [B Impact] Assessment was quite unwieldy in the beginning but has gotten better and better each year.” This sentiment being consistent across all of the interviewees that had recertified at least once, and the lack of consideration paid towards decertifying by executives of B Corp Certified companies supports the conclusion made by the literature that the certification’s attrition rate has rapidly declined over time and further suggests that this decline in attrition may be due to improved user experience while navigating the certification (Cao, 2017; Martin, 2020). Beyond the general improvement of the B Impact Assessment, another explanation for this trend is the emergence of B Corp consulting as a rapidly growing industry. Of the Certified B Corps represented in the sample, all had received paid or unpaid B Corp consulting help for their original certification or one of their recertification efforts. As a catalyst for growth in the B Corp consulting industry, there now exist about one dozen B Impact Clinic programs, in which university students are given an experiential learning classroom experience where they consult with businesses seeking B Corp Certification. This free service for businesses not only drives adoption of the B Corp Certification by lowering barriers to entry with respect to the time, effort, and money required to successfully certify, but every year they also teach hundreds of university students the skills necessary to become a practicing B Corp consultant, further developing the workforce that could improve the certification experience for businesses as well as expediting the speed at which businesses can complete and submit the B Impact Assessment.

When inquiring into the role that executives believed B Lab plays in facilitating the B Corp Movement, all the interviewees who had not yet become certified were largely unaware of the role that B Lab played in the process, beyond creating and updating the B Impact Assessment. In contrast, all of the executives representing currently certified companies were aware of B Lab’s role in community-building, with many interviewees within this group sharing that a key reason for their adoption of the certification was the existence of the B Hive network, and the more informal networking opportunities for aspiring and current B Corps, which all connect the B Corp community together. Furthermore, the majority of these executives indicated that they had learned about the certification and gained interest in it first by becoming involved in the B Corp community. This supports Thompson’s findings that bottom-up, high-touch, networking-driven approaches to developing social venture ecosystems are generally more successful at reaching scale than approaches in which significant infrastructure is created prior to community engagement (2018). Validating the findings in Martin’s research, the majority of aspiring B Corp executives who were interviewed indicated that their main pain points with the certification process were the lack of support from B Lab and the greater B Corp ecosystem in completing and submitting the B Impact Assessment as well as the significant delay between submission of the assessment and notification of certification, which currently ranges from six to nine months (2020). Both of these prevalent pain points illustrate B Lab’s under-resourced status as a constraint to the growth of the B Corp Movement, and further demonstrate the importance of B Impact Clinics and B Corp consultants in relieving stress placed on B Lab by the rapidly increasing demand for the certification.

There were several noteworthy outliers across interviewee commentary on B Lab’s role in accelerating the B Corp Movement. Two executives from currently certified companies mentioned another company in their community that had decertified due to how time-consuming and expensive the recertification would have been for the company, supporting Martin’s findings that the recertification process was a key reason for attrition due to its being “highly cumbersome, complicated, and time consuming” (2020). However, one interviewee from a long-time Certified B Corp that is notably at a significantly more mature stage in the company’s growth than the decertified company mentioned earlier was, stated: “we love the recertification process, because it forces us to keep improving,” suggesting that Martin’s conclusion may be more applicable to SMEs who may not have the same organizational bandwidth to allocate to recertification, than to larger corporations (2020). Two executives of currently certified companies cited fear that an upcoming update to the B Corp Certification – which will be made in an effort to standardize the process of becoming a B Corp – would make the certification process far too easy, leading to dilution of the value of the certification both in overcoming legitimacy deficits and in serving as a differentiator for companies that achieve certification. Another executive of a currently certified company stated that rising anti-ESG sentiment may soon spread to the B Corp Movement as well, which would subsequently negatively affect the movement’s ability to maintain support from both sides of the political spectrum. This executive emphasized: “unless B Lab adjusts their language to be clear that profitability is an important consideration [in the assessment], they will not have a movement that everyone can identify with.”

Several executives from current and aspiring B Corps identified a major inhibitor in the movement being the lack of value-aligned, patient capital that is both tailored to the specific needs of social ventures and favors social ventures over traditional, shareholder primacy-driven ventures. Many of these interviewees expressed beliefs that the current venture capital model of funding companies only promotes ventures that have the potential to be billion-dollar companies and only promotes founders that are willing to exit their company, by selling it or by executing an IPO, in order to deliver returns to their investors. Many interviewees also expressed beliefs that most venture capitalists and angel investors do not have a clear understanding on what social ventures and B Corps are, and do not prioritize companies that operate on with a stakeholder-focused philosophy as opposed to a shareholder primacy philosophy. These responses validate findings by Thompson, who found that social ventures tend to struggle to find early-stage funding from angel investors and venture capitalists, even in geographic regions and industries that traditionally have a strong venture capital industry (2018). The comments made by the aforementioned executives also reflect Thompson’s findings that drivers for the growth in number of social ventures are infrastructural in nature, such as the existence and prevalence of impact angel groups and venture capitalists, social venture accelerators, and social venture entrepreneurship competitions (2018). Notably, the consistent response from these executives contradicts claims made in the B Corp Handbook that B Corps and Benefit Corps do not struggle more than traditional ventures in raising investment capital (Honeyman, 2019). However, all interviewees across this study stated either that their existing investors were either indifferent to their certification status or actively supportive of it, further validating Thompson’s conclusion that B Corp Certification aids companies in raising money from existing impact investors (2018). Overall, the feedback received on investor viewpoints with regard to the certification highlights two key inhibitors to the movement: little availability of impact capital and a scarcity of education on social ventures and B Corps across the general investor population. Thompson’s research identifies the latter as being a significant root cause of the former (2018). One interviewed executive of a Certified B Corp stated that the B Corp Certification “needs to get even more recognition across the business community but especially across everyday consumers, and [the B Corp Certification should] become comparable to ‘1% For The Planet,’” further elaborating that, “this will make the certification an even more powerful differentiator and stakeholder engagement tool for those who obtain it.” This insight would support the conclusion made by Grimes, who suggested that the B Corp Certification could present an opportunity for investors, in particular, to understand what a B Corp (and a social venture) is the same way they understand nonprofits and corporations (2018).

CONCLUSION

The B Corp Movement presents a promising opportunity to solve key problems in the social venture ecosystem, including the legitimacy deficit associated with claims made concerning social and environmental impact, the lack of a qualitative method for incorporating social and environmental performance improvements into businesses’ growth roadmaps, and the lack of awareness of the role social ventures play in society. Although the B Corp Movement is not yet widely recognized by the general consumer, the B Corp Certification has seen rapid adoption from the business community. The qualitative interviews and literature review revealed a number of potential avenues for accelerating the B Corp Movement and breaking bottlenecks that may inhibit the movement’s growth. These include education of investors on impact investing and the B Corp Certification, increased infrastructure available to social ventures and B Corps, the expansion of B Corp consultancies and B Impact Clinic programs, and the advent of new patient and value-aligned investment capital deployment structures that better support B Corps in scaling their impact and scaling their businesses. Systemic changes to economic incentive structures in the public markets that encourage long-term investing and stakeholder-focused business practices, such as those proposed by the Long Term Stock Exchange, may also serve as an accelerant to the B Corp Movement by allowing publicly traded companies to more readily participate in creating the sustainable and equitable impact that characterizes the movement. In order to educate the general consumer about the meaning of the certification, a handful have companies have championed the certification in marketing efforts; if this tactic were to grow in use over time, this would be likely to significantly elevate the awareness of the B Corp Certification and its meaning. Through further investigation into the growth drivers and inhibitors of the B Corp Movement, the emergence of true stakeholder capitalism may come to fruition more efficiently and holistically.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Baltes, B. B., & Rudolph, C. W. (2010). Examining the effect of negative Turkish stereotypes on evaluative workplace outcomes in Germany. Journal of Managerial Psychology, 25(2), 148–158. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683941011019357

Barton, D. (2013). Focusing Capital on the Long Term. McKinsey & Company.

Baskin, J. (1989). Dividend policy and the volatility of common stocks. The Journal of Portfolio Management, 15(3), 19–25. https://doi.org/10.3905/jpm.1989.409203

B Lab. (2023). B Corp certification demonstrates a company's entire social and environmental impact. B Corp Certification demonstrates a company's entire social and environmental impact. Retrieved May 10, 2022, from https://www.bcorporation.net/en-us/certification

B Lab. (2023). Information about the pending B Corp program for start-ups and smaller companies. Information about the Pending B Corp program for start-ups and smaller companies. Retrieved February 22, 2022, from https://www.bcorporation.net/en-us/programs-and-tools/pending-b-corps/

B Lab. (2023). The B corp certification pathway for eligible private or public companies with $100M to $999m in annual revenue and with 10 or more subsidiaries operating in multiple countries. The B Corp Certification pathway for eligible private or public companies with $100M to $999M in annual revenue and with 10 or more subsidiaries operating in multiple countries. Retrieved February 21, 2022, from https://www.bcorporation.net/en-us/certification/large-enterprise-multinational/

Bauer, J., Umlas, E. (2015). Making corporations responsible: The parallel tracks of the B Corp movement and the business and Human Rights Movement. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2650136

Cao, K., Gehman, J., & Grimes, M. G. (2017). Standing out and Fiting in: Charting the emergence of certified B corporations by industry and Region. Advances in Entrepreneurship, Firm Emergence and Growth, 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1108/s1074-754020170000019001

Dorado, S. (2005). Institutional entrepreneurship, partaking, and convening. Organization Studies, 26(3), 385–414. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840605050873

Eccles, R., Ioannou, I., & Serafeim, G. (2012). The impact of corporate sustainability on organizational processes and performance. https://doi.org/10.3386/w17950

Farley, J., Burke, M., Flomenhoft, G., Kelly, B., Murray, D. F., Posner, S., Putnam, M., Scanlan, A., & Witham, A. (2013). Monetary and fiscal policies for a finite planet. Sustainability, 5(6), 2802–2826. https://doi.org/10.3390/su5062802

Furnari, S. (2014). Interstitial spaces: Microinteraction settings and the genesis of new practices between Institutional Fields. Academy of Management Review, 39(4), 439–462. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2012.0045

Gazzola, P., Grechi, D., Ossola, P., & Pavione, E. (2019). Certified Benefit Corporations as a new way to make sustainable business: The Italian example. Corporate Social Responsibility and Environmental Management. https://doi.org/10.1002/csr.1758

Grimes, M. G., Gehman, J., & Cao, K. (2018). Positively deviant: Identity work through B corporation certification. Journal of Business Venturing, 33(2), 130–148. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusvent.2017.12.001

Honeyman, R., Jana, T., & Marcario, R. (2019). The B Corp Handbook: How You Can Use Business as a force for good (2nd ed.). Berrett-Koehler Publishers, Inc.

Hyde, J. (2021). Gender stereotyping of emotions in small businesses and entrepreneurial ventures. Journal of Business Diversity, 21(3). https://doi.org/10.33423/jbd.v21i3.4436

IPCC. (2021). Climate Change 2021: Impacts, Adaptation and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [M. D. Mastrandrea, P. J. Jacobson, S. F. B. Tavares (eds.)]. Cambridge University Press. https://report.ipcc.ch/ar6/wg2/IPCC_AR6_WGII_FullReport.pdf

Johnson, L. D. (2009). Dividends, duration, and price volatility. Canadian Journal of Administrative Sciences / Revue Canadienne Des Sciences De L'Administration, 8(1), 43–46. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1936-4490.1991.tb00662.x

Kim, S. (2017, June 22). Why companies are becoming B corporations. Harvard Business Review. Retrieved March 4, 2022, from https://hbr.org/2016/06/why-companies-are-becoming-b-corporations

KKS Advisors, Stewart Investors. (2017, April). B Corps Benefit Corporations Understanding the Implications for Companies and Investors. Squarespace. Retrieved February 19, 2022, from https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5143211de4b038607dd318cb/t/593e4f29e3df286fa0049a9d/1497255766635/B-Corps-Benefit-Corporations.pdf

Koenig, A. M., & Eagly, A. H. (2014). Evidence for the social role theory of stereotype content: Observations of groups’ roles shape stereotypes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 107(3), 371–392. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0037215

Konieczka, P., & Szyszka, A. (2014). Do investor preferences drive corporate dividend policy? International Journal of Management and Economics, 39(1), 70–81. https://doi.org/10.2478/ijme-2014-0022

Lambert, R. A. (1998). Customer satisfaction and future financial performance discussion of are nonfinancial measures leading indicators of financial performance? an analysis of customer satisfaction. Journal of Accounting Research, 36, 37. https://doi.org/10.2307/2491305

Lazonick, W. (2009). The new economy business model and the crisis of U.S. capitalism. Capitalism and Society, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.2202/1932-0213.1054

Marginson, D., McAulay, L., Roush, M., & van Zijl, T. (2009). Performance measures and short-termism: An exploratory study. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.2028761

Marquis, C. (2020). The B Corp Movement Goes Big. Stanford Social Innovation Review.

Martin, C. (2020). An investigation into the reasons organizations forgo their B Corp Certification Status. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3714514

Moroz, P. W., Gamble, E. N. (2021). Business Model Innovation as a window into adaptive tensions: Five paths on the B Corp Journey. Journal of Business Research, 125, 672–683. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2020.01.046

Muiru, O. W. (2019). The B movement in East Africa: A shift in the culture of business. African Evaluation Journal, 7(1). https://doi.org/10.4102/aej.v7i1.333

Park, K. C. (2018). B the change: Social companies, B Corps, and benefit corporations (dissertation). ProQuest Dissertations Theses, Ann Arbor, MI.

Pearlstein, S. (2014). Social Capital, Corporate Purpose and the Revival of American Capitalism. Center for Effective Public Management at Brookings.

Rawhouser, H., Cummings, M., & Crane, A. (2015). Benefit corporation legislation and the emergence of a social hybrid category. California Management Review, 57(3), 13–35. https://doi.org/10.1525/cmr.2015.57.3.13

Sliwka, D. (2007). Trust as a signal of a social norm and the hidden costs of Incentive Schemes. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.932028

Sneirson, J. (2009). Green Is Good: Sustainability, Profitability, and a New Paradigm for Corporate Governance. Iowa Law Review.

Stout, L. (2018). New thinking on "shareholder primacy". https://doi.org/10.31228/osf.io/fn2gu

Stubbs, W. (2017). Characterising B Corps as a sustainable business model: An exploratory study of B corps in Australia. Journal of Cleaner Production, 144, 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jclepro.2016.12.093

Thébaud, S. (2016). Passing up the job: The role of gendered organizations and families in the entrepreneurial career process. Entrepreneurship Theory and Practice, 40(2), 269–287. https://doi.org/10.1111/etap.12222

Thompson, T. A., Purdy, J. M., & Ventresca, M. J. (2018). How entrepreneurial ecosystems take form: Evidence from Social Impact Initiatives in Seattle. Strategic Entrepreneurship Journal, 12(1), 96–116. https://doi.org/10.1002/sej.1285

Wilson, F., Post, J. E. (2011). Business models for people, planet (profits): Exploring the phenomena of social business, a market-based approach to social value creation. Small Business Economics, 40(3), 715–737. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11187-011-9401-0

World Economic Forum. (2016, October 26). Corporations, not countries, dominate the list of the world’s biggest economic entities. World Economic Forum Agenda. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2016/10/corporations-not-countries-dominate-the-list-of-the-world-s-biggest-economic-entities/